Loop alignment in .NET 6

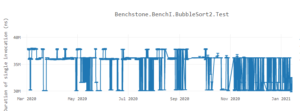

When writing a software, developers try their best to maximize the performance they can get from the code they have baked into the product. Often, there are various tools available to the developers to find that last change they can squeeze into their code to make their software run faster. But sometimes, they might notice slowness in the product because of a totally unrelated change. Even worse, when measured the performance of a feature in a lab, it might show instable performance results that looks like the following BubbleSort graph1. What could possibly be introducing such flakiness in the performance?

To understand this behavior, first we need to understand how the machine code generated by the compiler is executed by the CPU. CPU fetch the machine code (also known as instruction stream) it need to execute. The instruction stream is represented as series of bytes known as opcode. Modern CPUs fetch the opcodes of instructions in chunks of 16-bytes (16B), 32-bytes (32B) or 64-bytes (64B). The CISC architecture has variable length encoding, meaning the opcode representing each instruction in the instruction stream is of variable length. So, when the Fetcher fetches a single chunk, it doesn’t know at that point the start and end of an instruction. From the instruction stream chunk, CPU’s Pre-decoder identifies the boundary and lengths of instruction, while the Decoder decodes the meaning of the opcodes of those individual instructions and produce micro-operations (μops) for each instruction. These μops are fed to the Decoder Stream Buffer (DSB) which is a cache that indexes μops with the address from where the actual instruction was fetched. Before doing a fetch, CPU first checks if the DSB contains the μops of the instruction it wants to fetch. If it is already present, there is no need to do a cycle of instruction fetching, pre-decoding and decoding. Further, there also exist Loop Stream Detector (LSD) that detects if a stream of μops represents a loop and if yes, it skips the front-end fetch and decode cycle and continue executing the μops until a loop misprediction happens.

Code alignment

Let us suppose we are executing an application on a CPU that fetches instruction in 32B chunks. The application has a method having a hot loop inside it. Every time the application is run, the loop’s machine code is placed at different offset. Sometimes, it could get placed such that the loop body does not cross the 32B address boundary. In those cases, the instruction fetcher could fetch the machine code of the entire loop in one round. On the contrary, if the loop’s machine code is placed such that the loop body crosses the 32B boundary, the fetcher would have to fetch the loop body in multiple rounds. A developer cannot control the variation in fetching time because that is dependent on where the machine code of the loop is present. In such cases, you could see instability in the method’s performance. Sometimes, the method runs faster because the loop was aligned at fetcher favorable address while other times, it can show slowness because the loop was misaligned and fetcher spent time in fetching the loop body. Even a tiny change unrelated to the method body (like introducing a new class level variable, etc.) can affect the code layout and misalign the loop’s machine code. This is the pattern that can be seen in bubble sort benchmark above. This problem is mostly visible in CISC architectures because of variable length encoding of the instructions. The RISC architectures CPUs like Arm have fixed length encoding and hence might not see such a large variance in the performance.

To solve this problem, compilers perform alignment of the hot code region to make sure the code’s performance remains stable. Code alignment is a technique in which one or more NOP instructions are added by the compiler in the generated machine code just before the hot region of the code so that the hot code is shifted to an address that is mod(16), mod(32) or mod(64). By doing that, maximum fetching of the hot code can happen in fewer cycles. Study shows that by performing such alignments, the code can benefit immensely. Additionally, the performance of such code is stable since it is not affected by the placement of code at misaligned address location. To understand the code alignment impact in details, I would highly encourage to watch the Causes of Performance Swings due to Code Placement in IA talk given by Intel’s engineer Zia Ansari at 2016 LLVM Developer’s Meeting.

In .NET 5, we started aligning methods at 32B boundary. In .NET 6, we have added a feature to perform adaptive loop alignment that adds NOP padding instructions in a method having loops such that the loop code starts at mod(16) or mod(32) memory address. In this blog, I will describe the design choices we made, various heuristics that we accounted for and the analysis and implication we studied on 100+ benchmarks that led us to believe that our current loop alignment algorithm will be beneficial in stabilizing and improving the performance of .NET code.

Heuristics

When we started working on this feature, we wanted to accomplish the following things:

- Identify hot inner most loop(s) that executes very frequently.

- Add

NOPinstructions before the loop code such that the first instruction within the loop falls on 32B boundary.

Below is an example of a loop IG04~IG05 that is aligned by adding 6-bytes of align instruction. In this post, although I will represent the padding as align [X bytes] in the disassembly, we actually emit multi-byte NOP for the actual padding.

...

00007ff9a59ecff6 test edx, edx

00007ff9a59ecff8 jle SHORT G_M22313_IG06

00007ff9a59ecffa align [6 bytes]

; ............................... 32B boundary ...............................

G_M22313_IG04:

00007ff9a59ed000 movsxd r8, eax

00007ff9a59ed003 mov r8d, dword ptr [rcx+4*r8+16]

00007ff9a59ed008 cmp r8d, esi

00007ff9a59ed00b jge SHORT G_M22313_IG14

G_M22313_IG05:

00007ff9a59ed00d inc eax

00007ff9a59ed00f cmp edx, eax

00007ff9a59ed011 jg SHORT G_M22313_IG04A simple approach would be to add padding to all the hot loops. However, as I will describe in Memory cost section below, there is a cost associated with padding all the loops of method. There are lot of considerations that we need to take into account to get stable performance boost for the hot loops, and ensure that the performance is not downgraded for loops that don’t benefit from padding.

Alignment boundary

Depending on the design of processors the software running on them benefit more if the hot code is aligned at 16B, 32B or 64B alignment boundary. While the alignment should be in multiples of 16 and most recommended boundary for major hardware manufacturers like Intel, AMD and Arm is 32 byte, we had 32 as our default alignment boundary. With adaptive alignment (controlled using COMPlus_JitAlignLoopAdaptive environment variable and is set to be 1 by default), we will try to align a loop at 32 byte boundary. But if we do not see that it is profitable to align a loop on 32 byte boundary (for reasons listed below), we will try to align that loop at 16 byte boundary. With non-adaptive alignment (COMPlus_JitAlignLoopAdaptive=0), we will always try to align a loop to a 32 byte alignment by default. The alignment boundary can also be changed using COMPlus_JitAlignLoopBoundary environment variable. Adaptive and non-adaptive alignment differs by the amount of padding bytes added, which I will discuss in Padding amount section below.

Loop selection

There is a cost associated with a padding instruction. Although NOP instruction is cheap, it takes few cycles to fetch and decode it. So, having too many NOP or NOP instructions in hot code path can adversely affect the performance of the code. Hence, it will not be appropriate to align every possible loop in a method. That is the reason, LLVM has -align-all-* or gcc has -falign-loops flags to give the control to developers, to let them decide which loops should be aligned. Hence, the foremost thing that we wanted to do is to identify the loops in the method that will be most beneficial with the alignment. To start with, we decided to align just the non-nested loops whose block-weight meets a certain weight threshold (controlled by COMPlus_JitAlignLoopMinBlockWeight). Block weight is a mechanism by which the compiler knows how frequently a particular block executes, and depending on that, performs various optimizations on that block. In below example, j-loop and k-loop are marked as loop alignment candidates, provided they get executed more often to satisfy the block weight criteria. This is done in optIdentifyLoopsForAlignment method of the JIT.

If a loop has a call, the instructions of caller method will be flushed and those of callee will be loaded. In such case, there is no benefit in aligning the loop present inside the caller. Therefore, we decided not to align loops that contains a method call. Below, l-loop, although is non-nested, it has a call and hence we will not align it. We filter such loops in AddContainsCallAllContainingLoops.

void SomeMethod(int N, int M) {

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

// j-loop is alignment candidate

for (int j = 0; j < M; j++) {

// body

}

}

if (condition) {

return;

}

// k-loop is alignment candidate

for (int k = 0; k < M + N; k++) {

// body

}

for (int l = 0; l < M; l++) {

// body

OtherMethod();

}

}Once loops are identified in early phase, we proceed forward with advanced checks to see if padding is beneficial and if yes, what should be the padding amount. All those calculations happen in emitCalculatePaddingForLoopAlignment.

Loop size

Aligning a loop is beneficial if the loop is small. As the loop size grows, the effect of padding disappears because there is already lot of instruction fetching, decoding and control flow happening that it does not matter the address at which the first instruction of a loop is present. We have defaulted the loop size to 96 bytes which is 3 X 32-byte chunks. In other words, any inner loop that is small enough to fit in 3 chunks of 32B each, will be considered for alignment. For experimentation, that limit can be changed using COMPlus_JitAlignLoopMaxCodeSize environment variable.

Aligned loop

Next, we check if the loop is already aligned at the desired alignment boundary (32 byte or 16 byte for adaptive alignment and 32 byte for non-adaptive alignment). In such cases, no extra padding is needed. Below, the loop at IG10 starts at address 0x00007ff9a91f5980 == 0 (mod 32) is already at desired offset and no extra padding is needed to align it further.

00007ff9a91f597a cmp dword ptr [rbp+8], r8d

00007ff9a91f597e jl SHORT G_M24050_IG12

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (jl: 0) 32B boundary ...............................

00007ff9a91f5980 align [0 bytes]

G_M24050_IG10:

00007ff9a91f5980 movsxd rdx, ecx

00007ff9a91f5983 mov r9, qword ptr [rbp+8*rdx+16]

00007ff9a91f5988 mov qword ptr [rsi+8*rdx+16], r9

00007ff9a91f598d inc ecx

00007ff9a91f598f cmp r8d, ecx

00007ff9a91f5992 jg SHORT G_M24050_IG10We have also added a “nearly aligned loop” guard. There can be loops that do not start exactly at 32B boundary, but they are small enough to entirely fit in a single 32B chunk. All the code of such loops can be fetched with a single instruction fetcher request. In below example, the instructions between the two 32B boundary (marked with 32B boundary) fits in a single chunk of 32 bytes. The loop IG04 is part of that chunk and its performance will not improve if we add extra padding to it to make the loop start at 32B boundary. Even without padding, the entire loop will be fetched anyway in a single request. Hence, there is no point aligning such loops.

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (mov: 3) 32B boundary ...............................

00007ff9a921a903 call CORINFO_HELP_NEWARR_1_VC

00007ff9a921a908 xor ecx, ecx

00007ff9a921a90a mov edx, dword ptr [rax+8]

00007ff9a921a90d test edx, edx

00007ff9a921a90f jle SHORT G_M24257_IG05

00007ff9a921a911 align [0 bytes]

G_M24257_IG04:

00007ff9a921a911 movsxd r8, ecx

00007ff9a921a914 mov qword ptr [rax+8*r8+16], rsi

00007ff9a921a919 inc ecx

00007ff9a921a91b cmp edx, ecx

00007ff9a921a91d jg SHORT G_M24257_IG04

G_M24257_IG05:

00007ff9a921a91f add rsp, 40

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (add: 3) 32B boundary ...............................This was an important guard that we added in our loop alignment logic. Without this, imagine a loop of size 20 bytes that starts at offset mod(32) + 1. To align this loop, it needed padding of 31 bytes which might not be beneficial in certain scenarios where 31 byte NOP instructions are on hot code path. The “nearly aligned loop” protects us from such scenarios.

The “nearly aligned loop” check is not restrictive to just small loop that fits in a single 32B chunk. For any loop, we calculate the minimum number of chunks needed to fit the loop code. Now, if the loop is already aligned such that it occupies those minimum number of chunks, then we can safely ignore padding the loop further because padding will not make it any better.

In below example, the loop IG04 is 37 bytes long (00007ff9a921c690 - 00007ff9a921c66b = 37). It needs minimum 2 blocks of 32B chunk to fit. If the loop starts anywhere between mod(32) and mod(32) + (64 - 37), we can safely skip the padding because the loop is already placed such that its body will be fetched in 2 request (32 bytes in 1st request and 5 bytes in next request).

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (xor: 2) 32B boundary ...............................

00007ff9a921c662 mov r12d, dword ptr [r14+8]

00007ff9a921c666 test r12d, r12d

00007ff9a921c669 jle SHORT G_M11250_IG07

00007ff9a921c66b align [0 bytes]

G_M11250_IG04:

00007ff9a921c66b cmp r15d, ebx

00007ff9a921c66e jae G_M11250_IG19

00007ff9a921c674 movsxd rax, r15d

00007ff9a921c677 shl rax, 5

00007ff9a921c67b vmovupd ymm0, ymmword ptr[rsi+rax+16]

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (movupd: 1) 32B boundary ...............................

00007ff9a921c681 vmovupd ymmword ptr[r14+rax+16], ymm0

00007ff9a921c688 inc r15d

00007ff9a921c68b cmp r12d, r15d

00007ff9a921c68e jg SHORT G_M11250_IG04

G_M11250_IG05:

00007ff9a921c690 jmp SHORT G_M11250_IG07

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (xor: 1) 32B boundary ...............................To recap, so far, we have identified the hot nested loops in a method that needs padding, filtered out the ones that has calls, filtered the ones that are big than our threshold and verified if the first instruction of the loop is placed such that extra padding will align that instruction at the desired alignment boundary.

Padding amount

To align a loop, NOP instructions need to be inserted before the loop starts so that the first instruction of the loop starts at an address which is mod(32) or mod(16). It can be a design choice on how much padding we need to add to align a loop. E.g., for aligning a loop to 32B boundary, we can choose to add maximum padding of 31 bytes or can have a limitation on the padding amount. Since padding or NOP instructions are not free, they will get executed (either as part of the method flow or if the aligned loop is nested inside another loop) and hence we need to make a careful choice of how much padding should be added. With non-adaptive approach, if an alignment needs to happen at N bytes boundary, we will try to add at most N-1 bytes to align the first instruction of the loop. So, with 32B or 16B non-adaptive technique, we will try to align a loop to 32-byte or 16-byte boundary by adding at most 31 bytes or 15 bytes, respectively.

However, as mentioned above, we realized that adding lot of padding regresses the performance of the code. For example, if a loop which is 15 bytes long, starts at offset mod(32) + 2, with non-adaptive 32B approach, we would add 30 bytes of padding to align that loop to the next 32B boundary address. Thus, to align a loop that is 15 bytes long, we have added extra 30 bytes to align it. If the loop that we aligned was a nested loop, the processor would be fetching and decoding these 30 bytes NOP instructions on every iteration of outer loop. We have also increased the size of method by 30 bytes. Lastly, since we would always try to align a loop at 32B boundary, we might add more padding compared to the amount of padding needed, had we had to align the loop at 16B boundary. With all these shortcomings, we came up with an adaptive alignment algorithm.

In adaptive alignment, we would limit the amount of padding added depending on the size of the loop. In this technique, the biggest possible padding that will be added is 15 bytes for a loop that fits in one 32B chunk. If the loop is bigger and fits in two 32B chunks, then we would reduce the padding amount to 7 bytes and so forth. The reasoning behind this is that bigger the loop gets, it will have lesser effect of the alignment. With this approach, we could align a loop that takes 4 32B chunks if padding needed is 1 byte. With 32B non-adaptive approach, we would never align such loops (because of COMPlus_JitAlignLoopMaxCodeSize limit).

| Max Pad (bytes) | Minimum 32B blocks needed to fit the loop |

|---|---|

| 15 | 1 |

| 7 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 1 | 4 |

Next, because of padding limit, if we cannot get the loop to align to 32B boundary, the algorithm will try to align the loop to 16B boundary. We reduce the max padding limit if we get here as seen in the table below.

| Max Pad (bytes) | Minimum 32B blocks to fit the loop |

|---|---|

| 7 | 1 |

| 3 | 2 |

| 1 | 3 |

With the adaptive alignment model, instead of totally restricting the padding of a loop (because of padding limit of 32B), we will still try to align the loop on the next better alignment boundary.

Padding placement

If it is decided that padding is needed and we calculate the padding amount, the important design choice to make is where to place the padding instructions. In .NET 6, it is done naïvely by placing the padding instruction just before the loop starts. But as described above, that can adversely affect the performance because the padding instructions can fall on the execution path. A smarter way would be to detect some blind spots in the code before the loop and place it at such that the padding instruction do not get executed or are executed rarely. E.g., If we have an unconditional jump somewhere in the method code, we could add padding instruction after that unconditional jump. By doing this, we will make sure that the padding instruction is never executed but we still get the loop aligned at right boundary. Another place where such padding can be added is in code block or a block that executes rarely (based on Profile-Guided Optimization data). The blind spot that we select should be lexically before the loop that we are trying to align.

00007ff9a59feb6b jmp SHORT G_M17025_IG30

G_M17025_IG29:

00007ff9a59feb6d mov rax, rcx

G_M17025_IG30:

00007ff9a59feb70 mov ecx, eax

00007ff9a59feb72 shr ecx, 3

00007ff9a59feb75 xor r8d, r8d

00007ff9a59feb78 test ecx, ecx

00007ff9a59feb7a jbe SHORT G_M17025_IG32

00007ff9a59feb7c align [4 bytes]

; ............................... 32B boundary ...............................

G_M17025_IG31:

00007ff9a59feb80 vmovupd xmm0, xmmword ptr [rdi]

00007ff9a59feb84 vptest xmm0, xmm6

00007ff9a59feb89 jne SHORT G_M17025_IG33

00007ff9a59feb8b vpackuswb xmm0, xmm0, xmm0

00007ff9a59feb8f vmovq xmmword ptr [rsi], xmm0

00007ff9a59feb93 add rdi, 16

00007ff9a59feb97 add rsi, 8

00007ff9a59feb9b inc r8d

00007ff9a59feb9e cmp r8d, ecx

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (cmp: 1) 32B boundary ...............................

00007ff9a59feba1 jb SHORT G_M17025_IG31

In above example, we aligned loop IG31 with 4 bytes padding, but we have inserted the padding right before the first instruction of the loop. Instead, we can add that padding after the jmp instruction present at 00007ff9a59feb6b. That way, the padding will never be executed, but IG31 will still get aligned at desired boundary.

Memory cost

Lastly, there is a need to evaluate how much extra memory is allocated by the runtime for adding the extra padding before the loop. If the compiler aligns every hot loop, it can increase the code size of a method. There must be a right balance between the loop size, frequency of its execution, padding needed, padding placement to ensure only the loops that truly benefit with the alignment are padded. Another aspect is that the if the JIT, before allocating memory for the generated code, can evaluate how much padding is needed to align a loop, it will request precise amount of memory to accommodate the extra padding instruction. However, like in RyuJIT, we first generate the code (using our internal data structures), sum up the total instruction size and then determine the amount of memory needed to store the instructions. Next, it allocates the memory from runtime and lastly, it will emit and store the actual machine instructions in the allocated memory buffer. During code generation (when we do the loop alignment calculation), we do not know the offset where the loop will be placed in the memory buffer. In such case, we will have to pessimistically assume the maximum possible padding needed. If there are many loops in a method that would benefit from alignment, assuming maximum possible padding for all the loops would increase the allocation size of that method although the code size would be much smaller (depending on actual padding added).

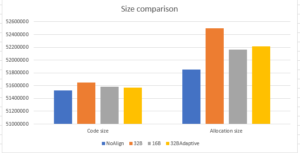

Below graph demonstrates the code size and allocation size’s impact due to the loop alignment. Allocation size represents the amount of memory allocated to store the machine code of all the .NET libraries methods while code size represents the actual amount of memory needed to store method’s machine code. The code size is lowest for 32BAdaptive technique. This is because we have cut off the padding amount depending on the loop size, as discussed before. So from memory perspective, 32BAdaptive wins.

Allocation size in above graph is higher than the code size for all the implementation because we accounted for maximum possible padding for every loop during allocation size calculation. Ideally, we wanted to have allocation size same as code size. Below is another view that demonstrates the difference between the allocation size and code size. The difference is highest for 32B non-adaptive implementation and lowest with 16B non-adaptive. 32B adaptive is marginally higher than 16B non-adaptive, but again since the overall code size is minimal as compared to 16B/32B non-adaptive, 32BAdaptive is the winner.

However, to make sure that we know precise amount of padding we are going to add before allocating the memory, we devised a work around. During code generation, we know that the method starts at offset 0(mod 32). We calculate the padding needed to align the loop and update the align instruction with that amount. Thus, we would allocate the memory considering the real padding and would not allocate memory for loops for which we do not need padding. This works if the estimated size of all the instructions during code generation of a method matches the actual size during emitting those instructions. Sometimes, during emitting, we realize that it is optimal to have shorter encoding for an instruction and that deviates the estimated vs. actual size of that instruction. We cannot afford to have this misprediction happen for instruction that falls before the loop that we are about to align, because that would change the placement of the loop.

In below example, the loop starts at IG05 and during code generation, we know that by adding padding of 1 byte, we can align that loop at 0080 offset. But during emitting the instruction, if we decide to encode instruction_1 such that it just takes 2 bytes instead of 3 bytes (that we estimated), the loop will start from memory address 00007ff9a59f007E. Adding 1 byte of padding would make it start at 00007ff9a59f007F which is not what we wanted.

007A instruction_1 ; size = 3 bytes

007D instruction_2 ; size = 2 bytes

IG05:

007F instruction_3 ; start of loop

0083 instruction_4

0087 instruction_5

0089 jmp IG05Hence, to account for this over-estimation of certain instructions, we compensate by adding extra NOP instructions. As seen below, with this NOP, our loop will continue to start at 00007ff9a59f007F and the padding of 1 byte will make it align at 00007ff9a59f0080 address.

00007ff9a59f007A instruction_1 ; size = 2 bytes

00007ff9a59f007C NOP ; size = 1 byte (compensation)

00007ff9a59f007D instruction_2 ; size = 2 bytes

IG05:

00007ff9a59f007F instruction_3 ; start of loop

00007ff9a59f0083 instruction_4

00007ff9a59f0087 instruction_5

0089 jmp IG05With that, we can precisely allocate memory for generated code such that the difference between allocated and actual code size is zero. In the long term, we want to address the problem of over-estimation so that the instruction size is precisely known during code generation and it matches during emitting the instruction.

Impact

Finally, let’s talk about the impact of this work. While I have done lots and lots of analysis to understand the loop alignment impact on our various benchmarks, I would like to highlight two graphs that demonstrates both, the increased stability as well as improved performance due to the loop alignment.

In below performance graph of Bubble sort, data point 1 represents the point where we started aligning methods at 32B boundary. Data point 2 represents the point where we started aligning inner loops that I described above. As you can see, the instability has reduced by heavy margin and we also gained performance.

Below is another graph of “LoopReturn” benchmark2 ran on Ubuntu x64 box where we see similar trend.

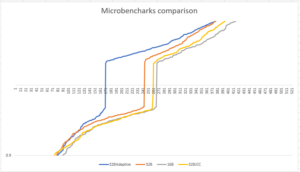

Below is the graph that shows the comparison of various algorithms that we tried to understand the loop alignment impact across benchmarks. The measurements in the graph are for microbenchmarks and in it, we compared the performance characteristics using various alignment techniques. 32B and 16B represents non-adaptive technique while 32BAdaptive represents 32B adaptive technique.

32B adaptive improves sooner after 171 benchmarks as compared to the next better approach which is 32B non-adaptive that gains performance after 241 benchmarks. We get maximum performance benefit sooner with 32B adaptive approach.

Edge cases

While implementing the loop alignment feature, I came across several edge cases that are worth mentioning. We identify that a loop needs alignment by setting a flag on the first basic block that is part of the loop. During later phases, if the loop gets unrolled, we need to make sure that we remove the alignment flag from that loop because it no longer represents the loop. Likewise, for other scenarios like loop cloning, or eliminating bogus loops, we had to make sure that we updated the alignment flag appropriately.

Future work

One of our planned future work is to add the “Padding placement” in blind spots as I described above. Additionally, we need to not just restrict aligning the inner loops but outer loops whose relative weight is higher than the inner loop. In below example, i-loop executes 1000 times, while the j-loop executes just 2 times in every iteration. If we pad the j-loop we will end up making the padded instruction execute 1000 times which can be expensive. Better approach would be to instead pad and align the i-loop.

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 2; j++) {

// body

}

}Lastly, the loop alignment is only enabled for x86 and x64 architecture, but we would like to take it forward and support Arm32 and Arm64 architectures as well.

Loop alignment in other compilers

For native or ahead of time compilers, it is hard to predict which loop will need alignment because the target address where the loop will be placed can only be known during runtime and not during ahead of time compilation. However, certain native runtimes at least give an option to the user to let them specify the alignment.

GCC

GCC provides -falign-functions attribute that the user can add on top of a function. More documentation can be seen on the gcc documentation page under “aligned” section. This will align the first instruction of every function at the specified boundary. It also provides options for -falign-loops, -falign-labels and -falign-jumps that will align all loops, labels or jumps in the entire code getting compiled. I did not inspect the GCC code, but looking at these options, it has several limitations. First, the padding amount is fixed and can anywhere between 0 and (N – 1) bytes. Second, the alignment will happen for the entire code base and cannot be restricted to a portion of files, methods, loops or hot regions.

LLVM

Same as GCC, dynamic alignment during runtime is not possible so LLVM too exposes an option of alignment choice to the user. This blog gives a good overview of various options available. One of the options that it gives is align-all-nofallthru-blocks which will not add padding instructions if the previous block can reach the current block by falling through because that would mean that we are adding NOPs in the execution path. Instead, it tries to add the padding at blocks that ends with unconditional jumps. This is like what I mentioned above under “Padding placement”.

Conclusion

Code alignment is a complicated mechanism to implement in a compiler and it is even harder to make sure that it optimizes the performance of a user code. We started with a simple problem statement and expectation, but during implementation, had to conduct various experiments to ensure that we cover maximum possible cases where the alignment would benefit. We also had to take into account that the alignment does not affect the performance adversely and devised mechanism to minimize such surface areas. I owe a big thanks to Andy Ayers who provided me guidance and suggested some great ideas during the implementation of loop alignment.

References

- BubbleSort2 benchmark is part of .NET’s micro-benchmarks suite and the source code is in dotnet/performance repository. Results taken in .NET perf lab can be seen on BubbleSort2 result page.

- LoopReturn benchmark is part of .NET’s micro-benchmarks suite and the source code is in dotnet/performance repository. Results taken in .NET perf lab can be seen on LoopReturn result page.

The post Loop alignment in .NET 6 appeared first on .NET Blog.

source https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/loop-alignment-in-net-6/