A friend once quipped to me that “computer science is entirely about sorting and searching”. While that’s a gross overgeneralization, there’s a grain of truth to it. Searching is, in one way, shape, or form, at the heart of many workloads, and it’s so important that multiple domain-specific languages have been created over the years to ease the task of expressing searches. Arguably none is more ubiquitous than regular expressions.

A regular expression, or regex, is a string that enables a developer to express a pattern being searched for, making it a very common way to search text and to extract from the results key finds. Every major development platform has one or more regex libraries, either built into the platform or available as a separate library, and .NET is no exception. .NET’s System.Text.RegularExpressions namespace has been around since the early 2000s, introduced as part of .NET Framework 1.1, and is used by thousands upon thousands of .NET applications and services.

At the time it was introduced, it was a state-of-the-art design and implementation. Over the years, however, it didn’t evolve significantly, and it fell behind the rest of the industry. This was rectified in .NET 5, where we re-invested in making Regex very competitive, with many improvements and optimizations to its implementation (elaborated on in Regex Performance Improvements in .NET 5). However, those efforts didn’t expand much upon its functionality. Now with .NET 7, we’ve again heavily invested in improving Regex, for performance but also for significant functional enhancements.

In this post, we’ll explore many of these improvements to highlight why Regex in .NET 7 is an awesome choice for your text searching needs in .NET.

Table Of Contents

Backtracking (and RegexOptions.NonBacktracking)

There are multiple ways a regex engine (the thing that does the actual searching) can be implemented. Since the beginning of .NET’s Regex, it’s employed a “backtracking” engine, sometimes called a “regex-directed” engine. Such engines work the way you might logically think about performing a search in your head: try one thing, and if it fails, go back and try the next… hence, “backtracking”. For example, given a pattern "a{3}|b{4}", which says “match either three 'a' characters or four 'b' characters”, a backtracking engine will walk along the input text, and at each relevant position, first try to match three 'a's, and if it can’t, then try to match four 'b's. In doing so, it might end up needing to examine the same text multiple times. Backtracking engines are capable of supporting more than just “regular languages”, and are a very popular form of engine because they enable fully implementing features like backreferences and lookarounds. Such backtracking engines also can be incredibly efficient, in particular when the thing being searched for matches and does so with as few wrong tries along the way as possible.

The problem with backtracking engine performance isn’t the best-case or even the expected-case, however, but rather the worst-case. You can find explanations of “catastrophic backtracking” or “excessive backtracking” all over the internet. Most of them use nested loops as an example, however I find that it’s easier to reason about with alternations. Consider an expression like ^(\d\w|\w\d)$; this expression ensures you’re matching at the beginning of the input, then matches either a digit followed by a word character, or a word character followed by a digit, and then requires being at the end of the input. If you try to match this against the input "12a" (ASCII numbers are both digits and word characters), it will:

- Match

\d\w against "12".

- Try to match

$ but fail because it’s not at the end of the input, so backtrack to the last choice made.

- Match

\w\d against "12".

- Try to match

$ but fail because it’s not at the end of the input, so backtrack to the last choice made.

- There are no more choices left, so fail.

Seems simple enough, but now let’s copy-and-paste the alternation so there are two of them, and double the number of digits in the input, matching ^(\d\w|\w\d)(\d\w|\w\d)$ against "1234a". Now we find it performs roughly as follows:

- Match alternation 1’s

\d\w against "12".

- Match alternation 2’s

\d\w against "34".

- Try to match

$ but fail because it’s not at the end of the input, so backtrack to the last choice made.

- Match alternation 2’s

\w\d against "34".

- Try to match

$ but fail because it’s not at the end of the input, so backtrack to the last choice made. There are no more choices in the second alternation, so backtrack further.

- Match alternation 1’s

\w\d against "12".

- Match alternation 2’s

\d\w against "34"

- Try to match

$ but fail because it’s not at the end of the input, so backtrack to the last choice made.

- Match alternation 2’s

\w\d against "34".

- Try to match

$ but fail because it’s not at the end of the input, so backtrack to the last choice made.

- There are no more choices left, so fail.

Notice that by adding one more alternation, we actually doubled the number of steps in our matching operation. If we were to add one more alternation, we’d double it again. One more, double it again. And so on. And there in lies the rub. For every additional alternation we add here, each with two possible choices, we’re allowing the implementation to backtrack through two choices for each alternation, for each of which it needs to evaluate everything else, yielding an O(2^N) algorithm. That’s… bad.

We can actually see this in practice. Try running the following code (and after starting it, go get a cup of coffee), which is the expression we just talked about, except using a repeater to express multiple alternations rather than copy-and-pasting that subexpression multiple times:

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

var sw = new Stopwatch();

for (int i = 10; i <= 30; i++)

{

var r = new Regex($@"^(\w\d|\d\w)}$");

string input = new string('1', (i * 2) + 1);

sw.Restart();

r.IsMatch(input);

sw.Stop();

Console.WriteLine($"{i}: {sw.Elapsed.TotalMilliseconds:N}ms");

}

On my machine, I see numbers like this:

10: 0.14ms

11: 0.32ms

12: 0.62ms

13: 1.26ms

14: 2.43ms

15: 5.03ms

16: 9.82ms

17: 19.71ms

18: 40.12ms

19: 79.85ms

20: 152.44ms

21: 318.82ms

22: 615.87ms

23: 1,230.21ms

24: 2,436.38ms

25: 4,895.82ms

26: 9,748.99ms

27: 19,487.77ms

28: 39,477.51ms

29: 82,267.19ms

30: 160,748.51ms

Notice how at first it’s fast, but as we increase the number of alternations, it slows down exponentially, approximately doubling in execution time on every addition. By the time we get to 30 alternations, what once was fast is now taking more than two and a half minutes.

This is the whole reason .NET’s Regex introduced support for timeouts. In practice, most regular expressions and the inputs they’re provided do not result in this catastrophic behavior. But if you can’t trust that the pattern isn’t susceptible given the right (or, rather, wrong) input, a timeout serves as a stopgap to help mitigate the possibility of a “ReDoS” attack, a “Regex Denial-of-Service” where such catastrophic backtracking is taken advantage of to get the system to spin its wheels. Thus, Regex supports timeouts, and guarantees that it will only do at most O(n) work (where n is the length of the input) between timeout checks, thus enabling a developer to prevent such runaway execution. .NET also supports setting a global timeout, such that if a timeout isn’t set on an individual problematic expression, the app itself can mitigate any such concerns.

There’s another approach, however. I mentioned that some engines are backtracking, or “regex-directed”. Others, however, in particular ones that are ok eschewing more advanced features like backreferences, and that are interested in being able to make worst-case guarantees about execution time regardless of the pattern, can opt for a more traditional “input-directed” model based on the origins of regular expressions: finite automata.

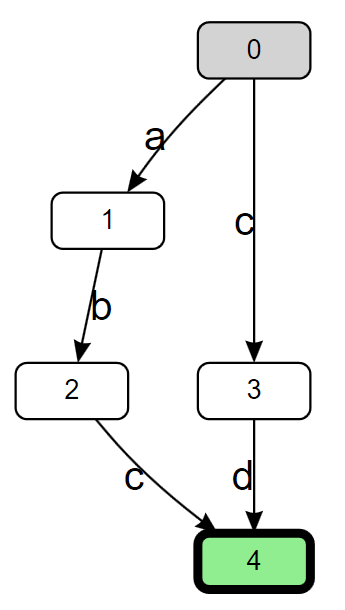

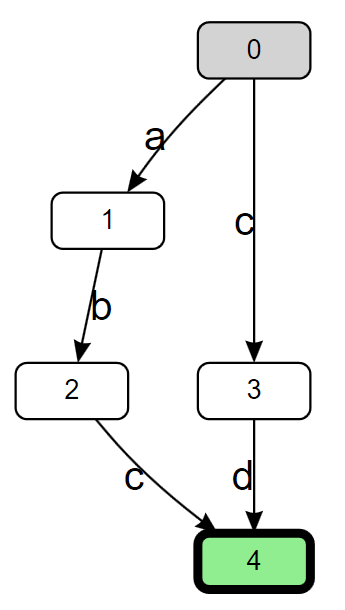

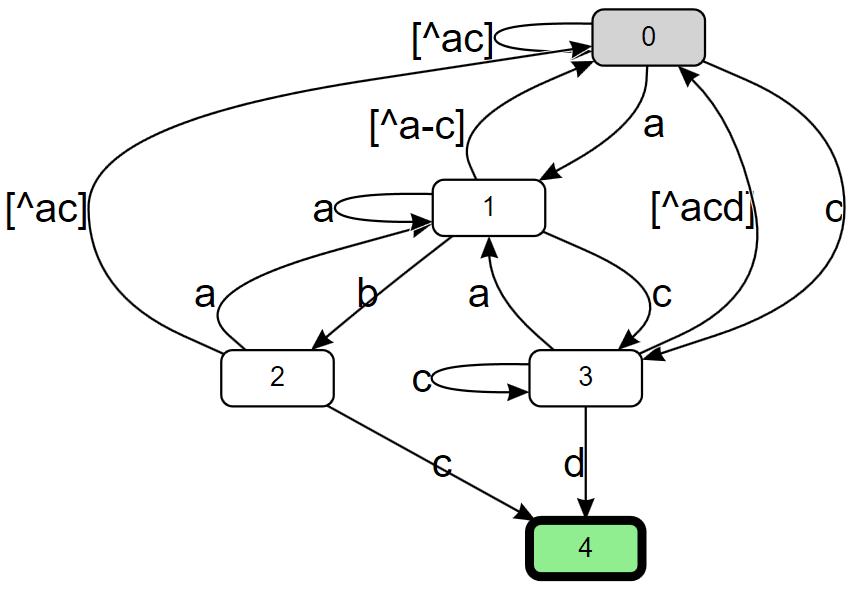

Imagine the regular expression being turned into a graph, where every construct in the pattern is represented as one or more nodes in a graph, and you can transition from one node to another based on the next character in the input. For example, consider the simple expression abc|cd. As a directed graph, this expression could look like this:

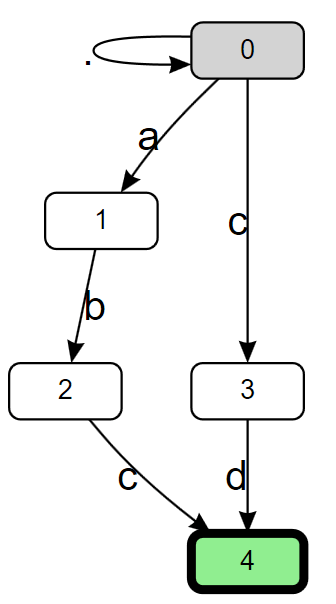

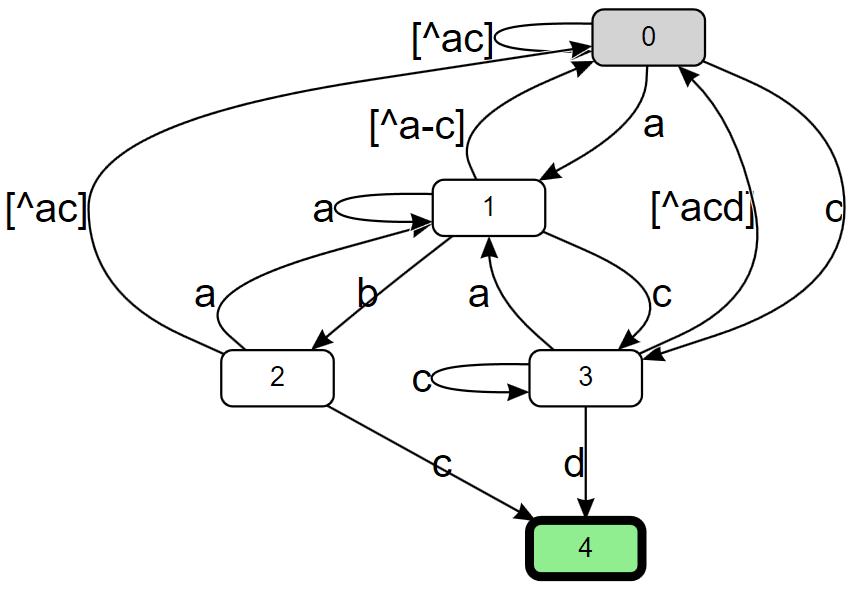

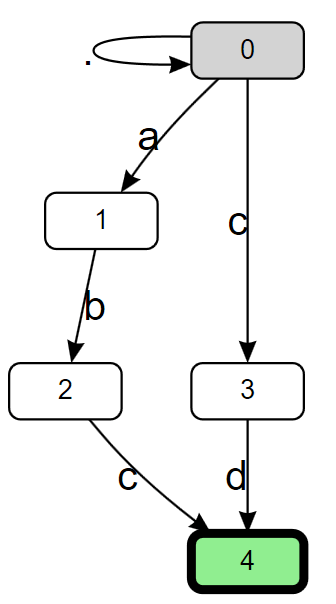

Here, the 0 node in the graph is the “start state”, the location in the graph at which we start the matching process. If the next character is a 'c', we transition to node 3. If the next character after that is a 'd', we transition to the final state of node 4 and declare a match. However, this graph really only represents the ability to match at a single fixed location in the input; if the initial character we read isn’t an 'a‘ or a 'c', nothing is matched. To address that, we can prefix the expression with a .*? lazy loop (here I’m using '.' to mean “match anything” rather than “match anything other than 'n'“, as if RegexOptions.Singleline was specified), to encapsulate the idea that we’re going to walk along the input until the first place we find "abc" or "cd" that matches. If we do that, we get almost the exact same graph, but this time with an extra transition from the start state back to the start state.

This graph represent’s what’s known as a “non-deterministic finite automata” (NFA). The “non-deterministic” part of it stems from that new transition we added from state 0 to state 0. Note that the transition is tagged as ., meaning it matches anything, and “anything” can include both 'a' and 'c', for which we already have transitions. That means if we’re in the start state and we read an 'a', we actually have two transitions we can take, one leading to node 1, and one leading back to node 0, which means after reading the 'a', we’re effectively in two nodes at the same time. A backtracking engine is often referred to as an NFA-based engine, as it’s logically walking the NFA graph, and when it comes to a point in the graph where it has to make a choice, it tries one choice, and if that ends up not matching, “backtracks” to the last choice it made, and goes a different way. As noted, this can result in exponential worst case processing time for some expressions.

But there are other ways to process an NFA. For example, rather than just considering ourselves in one node at a time, we can maintain a “current state” that’s the set of all nodes we’re currently “in”. For each character in the input we read, we enumerate all the states in our set, and for each, find all the new nodes we could transition to, creating our new set. This leads to O(n * m^2) worst-case processing time, where m is the number of nodes in the graph, and if you consider the pattern to be fixed and the only thing that’s dynamic is the input, then the size of the graph is constant, and this becomes O(n) worst-case processing time. For example, given the input "aaabc", we’d:

- Begin at the start state, such that our state set contains only that starting node: [0].

- Read

'a', find two transitions to nodes 0 and 1, yielding the new state set: [0, 1].

- Read

'a' again. From node 0, we again have two transitions to nodes 0 and 1, and from node 1, there’s no transition for 'a'. This again yields: [0, 1].

- Read

'a' again. And again, we end up with [0, 1].

- Read

'b'. There’s only one transition from node 0 back to itself, and there’s only one transition from node 1 for 'b' to node 2, yielding the new state set: [0, 2].

- Read

'c'. There’s now two transitions from node 0, one back to itself and one to node 3, and there’s one transition from node 2 to node 4: [0, 3, 4].

- Our state set includes the final state 4, so we’re done with a match.

There’s another form of finite automata, however, and that’s a “deterministic finite automata” (DFA). The key difference between a DFA and an NFA is the DFA is guaranteed to only have a single transition out of a node for a given input (so whereas every DFA is an NFA, not every NFA is a DFA). That makes a DFA really valuable for a regex engine, because it means the engine simply needs to make a single walk through the input (at least to determine whether there is a match): read the next character, transition to the next node, read the next character, transition to the next node, and on and on until either a final state is found (match) or it dead-ends, unable to transition out of the current node for the next input character (no match). This leads to O(n) worst-case processing time. The graph, however, is considerably more complex:

Notice how there are many more distinct transitions in this graph, to account for the fact that there’s only one possible transition out of a node for a given input, e.g. there are three transitions out of node 0, one for an 'a', one for a 'c', and one for everything other than 'a' or 'c'. Additionally, for any given state in the graph, we don’t have a lot of information about where we came from and what path we took to get there. That means a regex engine using this approach can employ such a graph to determine whether there is a match, but it then needs to do additional work to determine, for example, where the match starts, or the values of any subcaptures that might be in the pattern. Further, while every NFA can be transformed into a DFA, for an NFA with n nodes you can actually end up with a DFA with O(2^n) nodes. This leads most regex engines that use finite automata, like Google’s RE2 and Rust’s regex crate, to employ multiple strategies, for example starting out with a DFA that’s lazily computed (only adding nodes to the graph as they’re needed) and then falling back to an NFA-based model if the DFA-based model gets too large.

In .NET 7, developers using Regex now also have a choice to pick such an automata-based engine, using the new RegexOptions.NonBacktracking options flag, with an implementation grounded in the Symbolic Regex Matcher work from Microsoft Research (MSR). Going back to my previous catastrophic backtracking example, we can change the constructor call from:

var r = new Regex($@"^(\w\d|\d\w)}$");

to

var r = new Regex($@"^(\w\d|\d\w)}$", RegexOptions.NonBacktracking);

and now run the program again. Don’t bother going to get a cup of coffee this time. On my machine, I see numbers like this:

10: 0.10ms

11: 0.11ms

12: 0.10ms

13: 0.09ms

14: 0.09ms

15: 0.10ms

16: 0.10ms

17: 0.10ms

18: 0.12ms

19: 0.12ms

20: 0.13ms

21: 0.12ms

22: 0.13ms

23: 0.14ms

24: 0.14ms

25: 0.14ms

26: 0.15ms

27: 0.15ms

28: 0.17ms

29: 0.17ms

30: 0.17ms

The processing is now effectively linear in the length of the (short) input. And, actually, most of the cost here is in building the graph, which is done lazily as the implementation walks the graph and discovers it needs to transition to a node in the graph that hasn’t been computed yet (the implementation starts with a DFA, building out the nodes lazily, and at some point if the graph gets too big, it switches over dynamically to NFA-based processing, such that the graph then only grows linearly with the size of the pattern). If I subtly change the original program from doing:

sw.Restart();

r.IsMatch(input);

sw.Stop();

to instead doing:

r.IsMatch(input); // warm-up

sw.Restart();

r.IsMatch(input);

sw.Stop();

I then get numbers like these:

10: 0.00ms

11: 0.01ms

12: 0.00ms

13: 0.00ms

14: 0.00ms

15: 0.00ms

16: 0.01ms

17: 0.00ms

18: 0.00ms

19: 0.00ms

20: 0.00ms

21: 0.00ms

22: 0.01ms

23: 0.00ms

24: 0.00ms

25: 0.00ms

26: 0.00ms

27: 0.00ms

28: 0.00ms

29: 0.00ms

30: 0.00ms

With the graph fully computed already, we’re now seeing just the costs associated with execution, and it’s fast.

The new RegexOptions.NonBacktracking option doesn’t support everything the other built-in engines support. In particular, the option can’t be used in conjunction with RegexOptions.RightToLeft or RegexOptions.ECMAScript, and it doesn’t allow for the following constructs in the pattern:

Some of these restrictions are fairly fundamental to the implementation, while some of them could be relaxed in time should there be sufficient demand.

RegexOptions.NonBacktracking also has a subtle difference with regards to execution. .NET’s Regex has historically been unique amongst popular regex engines with regards to its behavior around captures. If a capture group is in a loop, most engines only provide the last matched value for that capture, but .NET’s Regex supports the notion of tracking all values a capture group inside a loop captured, and providing access to all of them. As of now, the new RegexOptions.NonBacktracking only supports providing the last, as do most other regex implementations. For example, this code:

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

foreach (RegexOptions option in new[] { RegexOptions.None, RegexOptions.NonBacktracking })

{

Console.WriteLine($"RegexOptions.{option}");

Console.WriteLine("----------------------------");

Match m = Regex.Match("a123b456c", @"a(\w)*b(\w)*c", option);

foreach (Group g in m.Groups)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Group: {g}");

foreach (Capture c in g.Captures)

{

Console.WriteLine($"\tCapture: {c}");

}

}

Console.WriteLine();

}

outputs:

RegexOptions.None

----------------------------

Group: a123b456c

Capture: a123b456c

Group: 3

Capture: 1

Capture: 2

Capture: 3

Group: 6

Capture: 4

Capture: 5

Capture: 6

RegexOptions.NonBacktracking

----------------------------

Group: a123b456c

Capture: a123b456c

Group: 3

Capture: 3

Group: 6

Capture: 6

Beyond that, most anything you do today with Regex you can do with RegexOptions.NonBacktracking. Note that the goal of NonBacktracking is not to be always faster than the backtracking engines. In fact, one of the reasons backtracking engines are so popular is they can be extremely fast in the best and even expected cases, and the .NET backtracking engines have been optimized with even more tricks and vectorization in .NET 7 to make them even faster than before in the best and typical use cases (I’ll discuss vectorization in more depth later in the post). NonBacktracking‘s bread-and-butter is to be fast (but not necessarily the fastest) for all cases, especially worst-case. Here’s an example to try to drive that home.

private Regex _backtracking = new Regex("a.*b", RegexOptions.Singleline | RegexOptions.Compiled);

private Regex _nonBacktracking = new Regex("a.*b", RegexOptions.Singleline | RegexOptions.NonBacktracking);

private string _input;

[Params(1, 2)]

public int Input { get; set; }

[GlobalSetup]

public void Setup()

{

_input = new string('a', 1000);

if (Input == 1)

{

_input += "b";

}

}

[Benchmark] public bool Backtracking() => _backtracking.IsMatch(_input);

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)] public bool NonBacktracking() => _nonBacktracking.IsMatch(_input);

Here we’re matching the expression a.*b against an input of one thousand 'a's followed by a 'b'. The backtracking engine implements that essentially by doing an IndexOf('a') to find the first place to try to match. Then as part of the match, it’ll compare the 'a', then jump to the end of the input (since .* with RegexOptions.Singleline matches everything), then LastIndexOf('b'), and will declare success. In contrast, the non-backtracking engine will read a character in the input, look in a transition table to determine the next node to transition to, move to that node, and will rinse and repeat until it finds a match. So in one case, we’re effectively doing fractional amounts of instructions per character (thanks to the vectorization), and in the other, we’re executing multiple instructions per character. The impact of that is evident in the resulting benchmark numbers:

| Method |

Input |

Mean |

Ratio |

| Backtracking |

1 |

43.08 ns |

0.008 |

| NonBacktracking |

1 |

5,541.18 ns |

1.000 |

For this input, the backtracking engine did effectively zero backtracking and was ~128x faster than the non-backtracking engine. But, now consider the second input, which is a thousand 'a's without a following 'b', such that it doesn’t match. The strategy employed by the non-backtracking engine will be exactly the same: read a character, transition to the next node, read a character, transition to the next node, and so on. But the backtracking engine will end up having to do much more work. It’ll start off the same way, doing an IndexOf('a') to find the next place to match, jumping to the end of the input, and doing a LastIndexOf('b')… but this time it won’t find one, so it’ll declare failure to match at position 0. It’ll then bump to position 1 and try again, finding the next 'a' at position 1, jumping to the end of the input, doing a LastIndexOf('b'), and not finding one. And it’ll bump again. And again. The result is it’ll end up doing O(n^2) work, and even though it’s vectorizing some of those operations, it’s still much more work, which again shows up in the numbers:

| Method |

Input |

Mean |

Ratio |

| Backtracking |

2 |

44,888.64 ns |

8.14 |

| NonBacktracking |

2 |

5,514.10 ns |

1.00 |

With the same pattern and just a different input, now the backtracking engine is ~8x slower than the non-backtracking engine rather than being ~128x faster. And importantly, the time the non-backtracking engine took is almost exactly the same with both inputs. Which is the whole point.

StringSyntaxAttribute.Regex

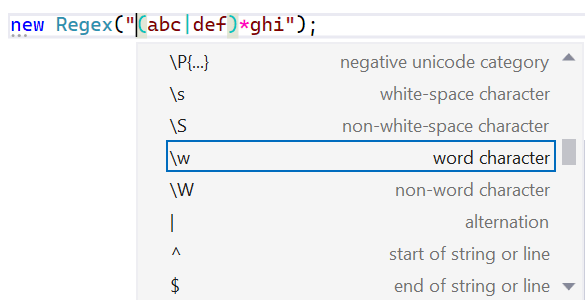

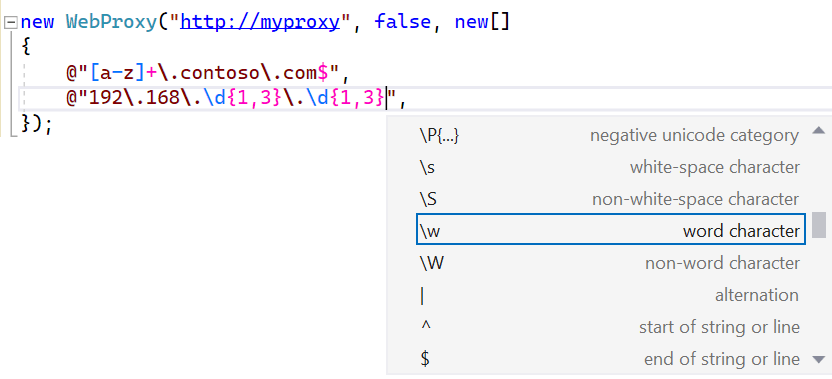

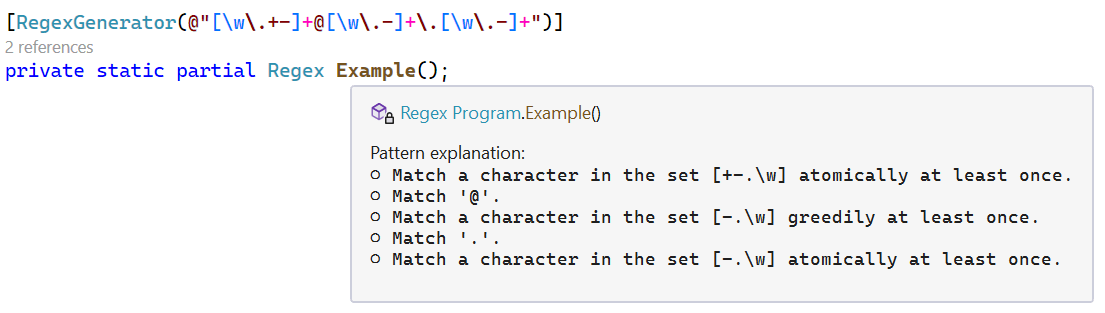

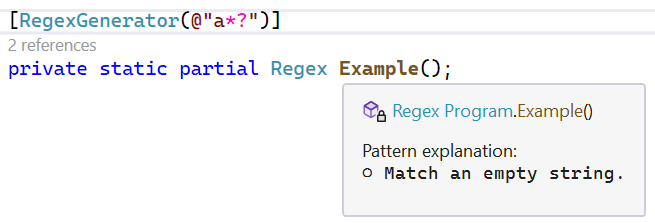

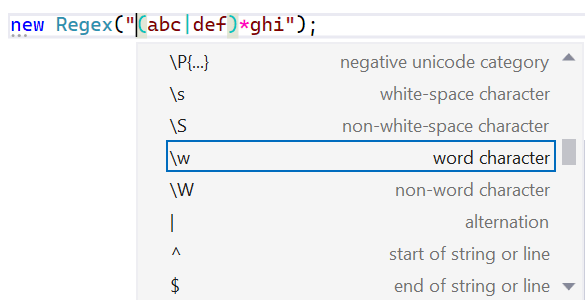

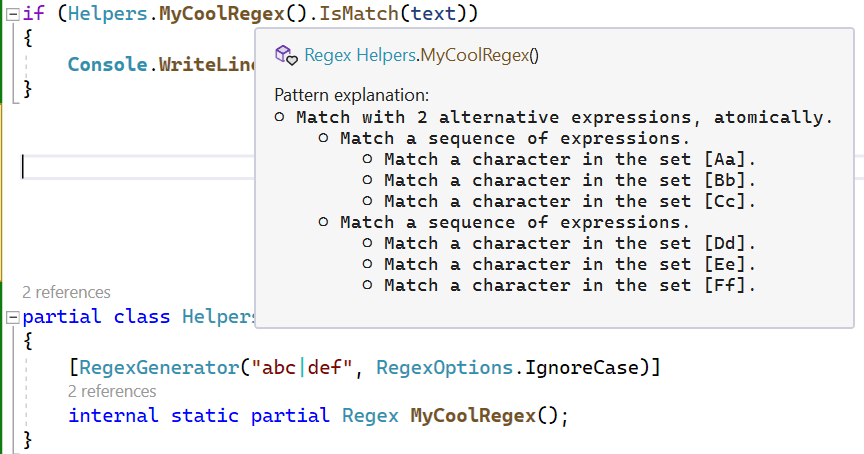

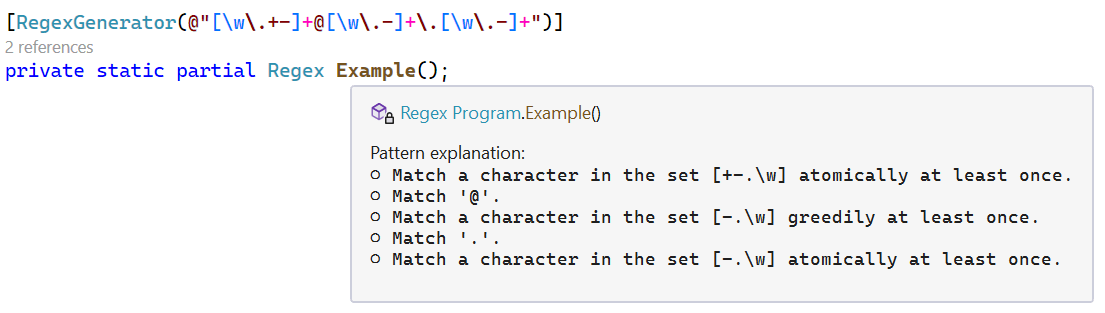

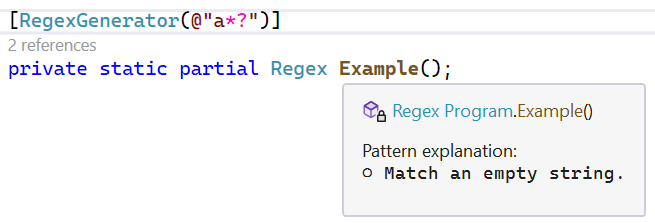

For developers using Regex, Visual Studio has a really nice feature that provides syntax colorization, syntax validation, and regex IntelliSense when working with regular expressions.

Historically, Visual Studio contained a hardcoded list of methods where it knew the arguments to those methods would be regular expressions. This isn’t scalable, however, with this treatment only afforded to Regex‘s constructors and static methods. This isn’t an issue unique to regular expressions, of course. There are many APIs that accept strings that need to adhere to specific syntaxes, for example passing JSON content into a method, or passing a DateTime format string into a ToString call, or any number of other domain-specific languages, and it’s not feasible for every tool that could meaningfully improve the developer experience around those APIs to hardcode the list of every possible API known to accept that syntax (nor to come up with heuristics for them).

Instead, .NET 7 introduces the new [StringSyntax(...)] attribute, which is used in .NET 7 on more than 350 string, string[], and ReadOnlySpan<char> parameters, properties, and fields to highlight to an interested tool what kind of syntax is expected to be passed or set. Now, any method that wants to indicate a string parameter accepts a regular expression can attribute it, e.g. void MyCoolMethod([StringSyntax(StringSyntaxAttribute.Regex)] string expression), and Visual Studio 2022 will provide the same syntax validation, syntax coloring, and IntelliSense that it provides for all the other Regex-related methods. For example, the WebProxy class provides a constructor that accepts an array of regex strings to be used as proxy bypasses; this string[] parameter is attributed in .NET 7 as [StringSyntax(StringSyntaxAttribute.Regex)], a fact that’s visible when using it in Visual Studio 2022:

String parameters, properties, and fields throughout the core .NET libraries now have been attributed to say whether they’re regular expressions, JSON, XML, composite format strings, URLs, numeric format strings, and on and on.

Case-insensitive matching (and RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)

It’s common with regular expressions to want to tell the engine to perform the match in a case-insensitive way. For example, you might write the pattern [a-z0-9] in order to match an ASCII letter or digit, but you also want the uppercase values to be included. To achieve that, most modern regex engines have support for the (?i) inline syntax which, when included in the pattern, tells the engine that everything after that token in its current subexpression should be treated in a case-insensitive manner. Thus:

(?i)[a-z0-9] is equivalent to [A-Za-z0-9](?i)[abc]d*efg is equivalent to [AaBbCc][Dd]*[Ee][Ff][Gg](?i)abc|def is equivalent to [Aa][Bb][Cc]|defabc|(?i)def is equivalent to abc|[Dd][Ee][Ff](?i)(abc|def) is equivalent to ([Aa][Bb][Cc]|[Dd][Ee][Ff])

.NET has long supported this inline syntax, but it’s also supported the RegexOptions.IgnoreCase option, which is equivalent to applying (?i), and thus case-insensitivity, to the whole pattern. .NET has also supported the RegexOptions.InvariantCulture option, which is only relevant when RegexOptions.IgnoreCase or (?i) is used and which changes exactly what values are considered case-equivalent.

In every version of .NET prior to .NET 7, this case-insensivity support is implemented via ToLower. When the Regex is constructed, the pattern is transformed such that every character in the pattern is lowercased, and then at match time, each time an input character is compared to something in the pattern, the input character is also ToLower‘d, and the lowercased values are compared. This support is functional, but there are some significant downsides to this implementation approach.

- Culture changes. By default, the “current” culture is used to perform the lowercasing, e.g.

CultureInfo.CurrentCulture.TextInfo.ToLower(c), and that’s relevant because culture impacts how characters change case. One of the most famous examples of this is the “Turkish i”. If you run (int)new CultureInfo("en-US").TextInfo.ToLower('I'), that will produce the value 105, the numerical value for the ASCII lowercase ‘i’, known in Unicode as “LATIN SMALL LETTER I”. If, however, you run the exact same code but changing the name of the culture to “tr-TR”, as in (int)new CultureInfo("tr-TR").TextInfo.ToLower('I'), that code will now produce the value 305, otherwise known in Unicode as the “LATIN SMALL LETTER DOTLESS I”. So culture matters (specifying RegexOptions.InvariantCulture simply serves to make the implementation use CultureInfo.InvariantCulture instead of CultureInfo.CurrentCulture). But there’s a functional issue here. I mentioned that the pattern is lowercased at construction time and the input is lowercased at match time, and that the current culture is used to perform that lowercasing… what happens if the culture changes between when the pattern is constructed and the input is matched? Nothing good. You then end up with inconsistencies, trying to compare one character lowercased according to one culture’s rules against another character lowercased according to another culture’s rules.

using System.Globalization;

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

CultureInfo.CurrentCulture = new CultureInfo("tr-TR");

var r = new Regex("İ", RegexOptions.IgnoreCase); // "construction time"

... // some other code

CultureInfo.CurrentCulture = new CultureInfo("en-US");

Console.WriteLine(r.IsMatch("I")); // "match time"

- ToLower overhead.

ToLower isn't super expensive, but it's also not free. Having to call ToLower on every character in order to process it means a comparatively high cost to processing each value. This overhead was decreased in previous versions of .NET, for example changing the code generated by RegexOptions.Compiled to cache the culture information so that rather than emitting the equivalent of CultureInfo.CurrentCulture.TextInfo.ToLower(c) on each comparison, it instead output _textInfo.ToLower(c). But even with such optimizations, this still contributes meaningfully to the gap in performance between case-sensitive and case-insensitive matching. Consider this example:

private Regex _r1 = new Regex("^[Aa]*$", RegexOptions.Compiled);

private Regex _r2 = new Regex("^a*$", RegexOptions.Compiled | RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

private string _input1 = new string('a', 100_000);

[Benchmark] public bool ManualSet1() => _r1.IsMatch(_input1);

[Benchmark] public bool IgnoreCase2() => _r2.IsMatch(_input1);

In theory, these two expressions should be identical, and functionally they are. But in the first case, with the set, in .NET 6 the compiled implementation will use code along the lines of (c == 'A') | (c == 'a') to match [Aa], whereas with the IgnoreCase version, in .NET 6 the compiled implementation will use code along the lines of _textInfo.ToLower(c) == 'a', such that on my machine I get results like this from the microbenchmark:

| Method |

Runtime |

Mean |

| ManualSet1 |

.NET 6 |

85.75 us |

| IgnoreCase2 |

.NET 6 |

235.40 us |

For two expressions that should be identical, ~3x is a sizeable difference, and it's all because of ToLower.

- Vectorization. There are two primary ways regular expressions end up being used: to validate whether some text fully matches a pattern, or to find occurrences of the pattern within some larger text. For the latter, it's critically important for performance to move as quickly as possible through the portions of text that can't possibly match in order to only spend more resources on the portions that might possibly match. The more comparisons that can be elided or done concurrently, the better off we are. And that's where vectorization comes into play. Vectorization is the approach of taking advantage of hardware instructions that support doing multiple things at the same time. Consider if I have 4 bytes and I want to compare all 4 of them to see if they're each 0xFF. I could write a for loop that walks each byte and compares each of the 4 against 0xFF, or I could treat the 4 contiguous bytes as if they were a 32-bit integer and just compare all 4 at the same time against 0xFFFFFFFF. Doing so will end up being ~4x faster. In a 64-bit process, I could do the same with 8 bytes, comparing against 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF, and it'd be ~8x faster. And modern hardware offers specialized instruction sets that support performing operations like this on 16, 32, or even 64 bytes at a time, and not just comparisons, but other more complicated operations as well. .NET exposes APIs for these "intrinsics", and exposes higher-level "vector" types like

Vector<T>, Vector128<T>, and Vector256<T> that make targeting these instructions easier, but the core libraries also use all of this support internally to vectorize operations like IndexOf. That way, a developer can just use IndexOf to perform their search and gain the full benefits of vectorization without having to manually write that vectorization code by hand. In .NET 5, Regex got in on this vectorization game by trying to use IndexOf and IndexOfAny to find the next location a pattern may match, if possible. But now consider this slightly tweaked version of the previously shown benchmark:

private Regex _r3 = new Regex("[Aa]+", RegexOptions.Compiled);

private Regex _r4 = new Regex("a+", RegexOptions.Compiled | RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

private string _input2 = new string('z', 100_000) + "AaAa";

[Benchmark] public bool ManualSet3() => _r3.IsMatch(_input2);

[Benchmark] public bool IgnoreCase4() => _r4.IsMatch(_input2);

Here we're searching a string of mostly 'z's that ends with "AaAa" against the pattern [Aa]+ or the IgnoreCase pattern a+. With the former, the implementation in .NET 6 could use IndexOfAny('A', 'a') to find the next possible start of a match, but because the case-insensitive implementation for IgnoreCase needs to call ToLower on every character, that implementation is forced to walk character by character through the input rather than vectorizing to process it in batches. The difference is stark:

| Method |

Runtime |

Mean |

| ManualSet3 |

.NET 6 |

4.312 us |

| IgnoreCase4 |

.NET 6 |

222.387 us |

All of these issues have led us to entirely reconsider how RegexOptions.IgnoreCase is handled. In .NET 7, we no longer implement RegexOptions.IgnoreCase by calling ToLower on each character in the pattern and each character in the input. Instead, all casing-related work is done when the Regex is constructed. Regex now uses a casing table to essentially answer the question "given the character 'c', what are all of the other characters it should be considered equivalent to under the selected culture?" So for example, in my current culture:

- Given the character

'a', it'll be determined to also be equivalent to 'A'.

- Given the "GREEK CAPITAL LETTER OMEGA" (

'u03A9'), it'll be determined to also be equivalent to the "GREEK SMALL LETTER OMEGA" ('u03C9'), and the "OHM SIGN" ('u2126').

From that, the implementation throws away the original IgnoreCase character and replaces it instead with a non-IgnoreCase set composed of all the equivalent characters. So, for example, given the pattern (?i)abcd, it'll replace that with [Aa][Bb][Cc][Dd]. This solves all three of the problems previously outlined:

- Culture changes. The only culture that matters is the one at the time of construction, since that's when the pattern is being transformed.

- ToLower overhead.

ToLower is no longer being used, so its overhead doesn't matter.

- Vectorization. We now have sets of known characters we can search for with methods like

IndexOfAny.

Now with .NET 7, I can run these benchmarks again:

private Regex _r1 = new Regex("^[Aa]*$", RegexOptions.Compiled);

private Regex _r2 = new Regex("^a*$", RegexOptions.Compiled | RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

private string _input1 = new string('a', 100_000);

[Benchmark] public bool ManualSet1() => _r1.IsMatch(_input1);

[Benchmark] public bool IgnoreCase2() => _r2.IsMatch(_input1);

private Regex _r3 = new Regex("[Aa]+", RegexOptions.Compiled);

private Regex _r4 = new Regex("a+", RegexOptions.Compiled | RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

private string _input2 = new string('z', 100_000) + "AaAa";

[Benchmark] public bool ManualSet3() => _r3.IsMatch(_input2);

[Benchmark] public bool IgnoreCase4() => _r4.IsMatch(_input2);

and we can see that the difference between the expressions has disappeared, since the IgnoreCase variants are being transformed to be identical to their counterparts.

| Method |

Runtime |

Mean |

| ManualSet1 |

.NET 6 |

85.75 us |

| IgnoreCase2 |

.NET 6 |

235.40 us |

| ManualSet3 |

.NET 6 |

4.312 us |

| IgnoreCase4 |

.NET 6 |

222.387 us |

|

|

|

| ManualSet1 |

.NET 7 |

47.167 us |

| IgnoreCase2 |

.NET 7 |

47.130 us |

| ManualSet3 |

.NET 7 |

4.147 us |

| IgnoreCase4 |

.NET 7 |

4.135 us |

It's also interesting to note that the first benchmark not only trippled in throughput to match the set-based expression, they both then further doubled in throughput, dropping from ~86us on .NET 6 to ~47us on .NET 7. More on that in a bit.

Now, several times I've stated that this eliminates the need for casing at match time. That's ~99.5% true. In almost every regex construct, the input text is compared against the pattern text, which we can compute IgnoreCase sets for at construction. Great. There is, however, a single construct which compares input text against input text: backreferences. Imagine I had the pattern "(?i)(\w\w\w)1". What happens when we try to match this against input text like "ABCabc". The engine will successfully match the "ABC" against the \w\w\w, storing that as the first capture, but the \1 backreference is itself IgnoreCase, which means it's now case-insensitively comparing the next three characters of the input against the already matched input "ABC", and it needs to somehow determine whether "ABC" is case-equivalent to "abc". Prior to .NET 7, it would just use ToLower on both, but we've moved away from that. So for IgnoreCase backreferences, not only will the casing tables be consulted at construction time, they'll also be used at match time. Thankfully, use of case-insensitive backreferences is fairly rare. In an open-source corpus of ~19,000 regular expressions gathered from appropriately-licensed nuget packages, only ~0.5% include a case-insensitive backreference.

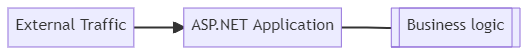

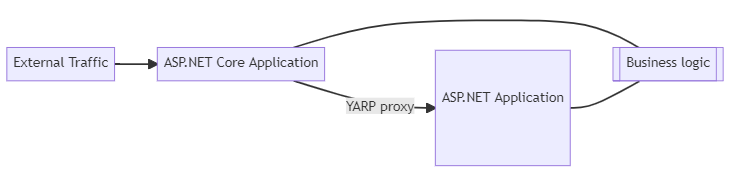

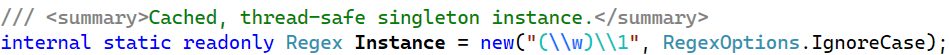

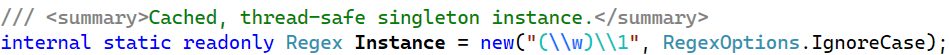

Source Generation

When you write new Regex("somepattern"), a few things happen. The specified pattern is parsed, both to ensure validity of the pattern and to transform it it into an internal RegexNode tree that represents the parsed regex. The tree is then optimized in various ways, transforming the pattern into a variation that's functionally equivalent but that can be more efficiently executed, and then that tree is written into a form that can be interpreted, a series of opcodes and operands that provide instructions to the internal RegexInterpreter engine on how to match. When a match is performed, the interpreter simply walks through those instructions, processing them against the input text. When instantiating a new Regex instance or calling one of the static methods on Regex, the interpreter is the default engine employed; we already saw how the new RegexOptions.NonBacktracking can be used to opt-in to the new non-backtracking engine, and RegexOptions.Compiled can be used to opt-in to a compilation-based engine.

When you specify RegexOptions.Compiled, prior to .NET 7, all of the same construction-time work would be performed. Then, the resulting instructions would be transformed further by the reflection-emit-based compiler into IL instructions that would be written to a few DynamicMethods. When a match was performed, those DynamicMethods would be invoked. This IL would essentially do exactly what the interpreter would do, except specialized for the exact pattern being processed. So for example, if the pattern contained [ac], the interpreter would see an opcode that essentially said "match the input character at the current position against the set specified in this set description" whereas the compiled IL would contain code that effectively said "match the input character at the current position against 'a' or 'c'". This special-casing and the ability to perform optimizations based on knowledge of the pattern are some of the main reasons specifying RegexOptions.Compiled yields much faster matching throughput than does the interpreter.

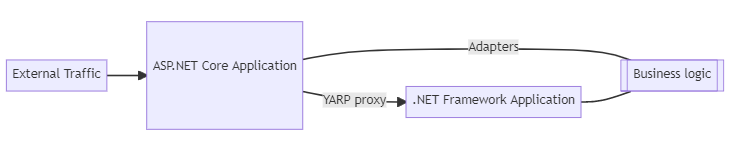

There are, however, several downsides to RegexOptions.Compiled. Most impactfully, it involves much more construction cost than does using the interpreter. Not only are all of the same costs paid as for the interpreter, but it then needs to compile that resulting RegexNode tree and generated opcodes/operands into IL, which adds non-trivial expense. And that generated IL further needs to be JIT-compiled on first use leading to even more expense at startup. RegexOptions.Compiled represents a fundamental tradeoff between overheads on first use and overheads on every subsequent use. The use of reflection emit also inhibits the use of RegexOptions.Compiled in certain environments; some operating systems don't permit dynamically generated code to be executed, and on such systems, Compiled will become a nop.

To help with these issues, the .NET Framework provides a method Regex.CompileToAssembly. This method enables the same IL that would have been generated for RegexOptions.Compiled to instead be written to a generated assembly on disk, and that assembly can then be referenced as a library from your app. This has the benefits of avoiding the startup overheads involved in parsing, optimizing, and outputting the IL for the expression, as that can all be done ahead of time rather than each time the app is invoked. Further, that assembly could be ahead-of-time compiled with a technology like ngen / crossgen, avoiding most of the associated JIT costs as well.

Regex.CompileToAssembly itself has problems, however. First, it was never particularly user friendly. The ergonomics of having to have a utility that would call CompileToAssembly in order to produce an assembly your app would reference resulted in relatively little use of this otherwise valuable feature. And on .NET Core, CompileToAssembly has never been supported, as it requires the ability to save reflection-emit code to assemblies on disk, which also isn't supported.

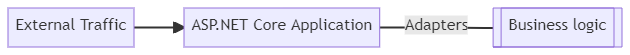

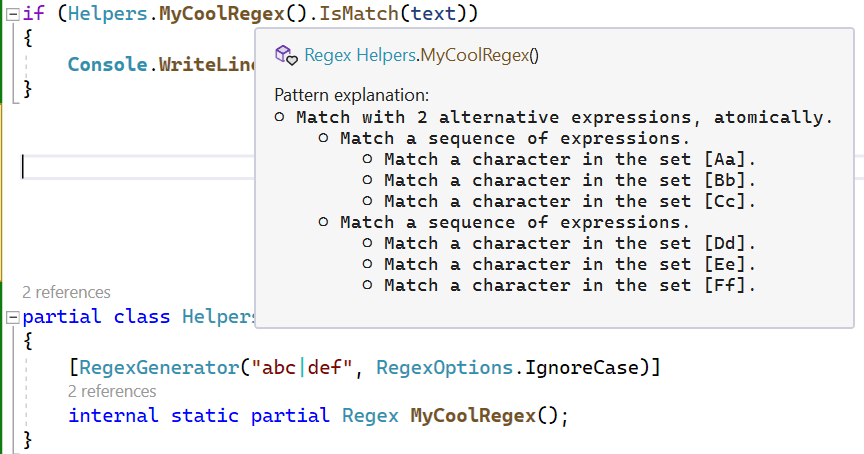

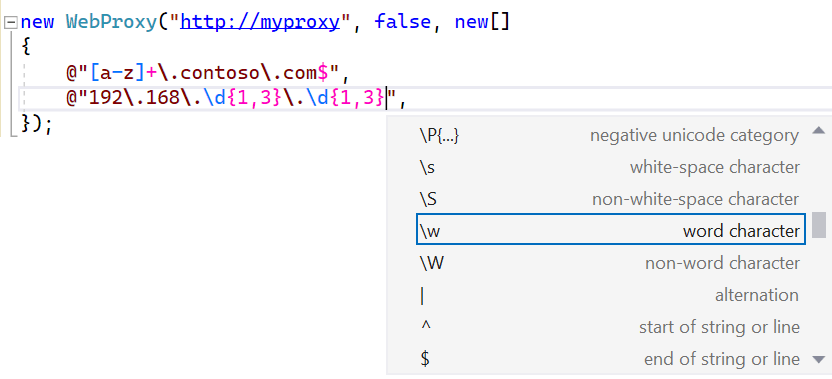

.NET 7 addresses all of this with the new RegexGenerator source generator. The original compiler for C# was implemented in C/C++. A decade ago, in the grand tradition of compilers being implemented in the language they compile, the "Roslyn" C# compiler was implemented in C#. As part of this, it exposed object models for the entire compilation pipeline, with APIs the compiler itself uses to parse and understand C# but that are also exposed for arbitrary code to use to do the same. It then also enabled components that could plug into the compiler itself, with the compiler handing these "analyzers" all of the information the compiler had built up about the code being compiled and allowing the analyzers to inspect the data and issue additional "diagnostics" (e.g. warnings). More recently, Roslyn also enabled source generators. Just like an analyzer, a source generator is a component that plugs into the compiler and is handed all of the same information as an analyzer, but in addition to being able to emit diagnostics, it can also augment the compilation unit with additional source code. The .NET 7 SDK includes a new source generator which recognizes use of the new RegexGeneratorAttribute on a partial method that returns Regex, and provides an implementation of that method which implements on your behalf all the logic for the Regex. For example, if previously you would have written:

private static readonly Regex s_myCoolRegex = new Regex("abc|def", RegexOptions.Compiled | RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

...

if (s_myCoolRegex.IsMatch(text) { ... }

you can now write that as:

[RegexGenerator("abc|def", RegexOptions.IgnoreCase)]

private static partial Regex MyCoolRegex();

...

if (MyCoolRegex().IsMatch(text) { ... }

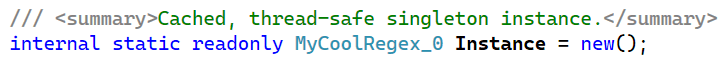

The generated implementation of MyCoolRegex() similarly caches a singleton Regex instance, so no additional caching is needed in consuming code.

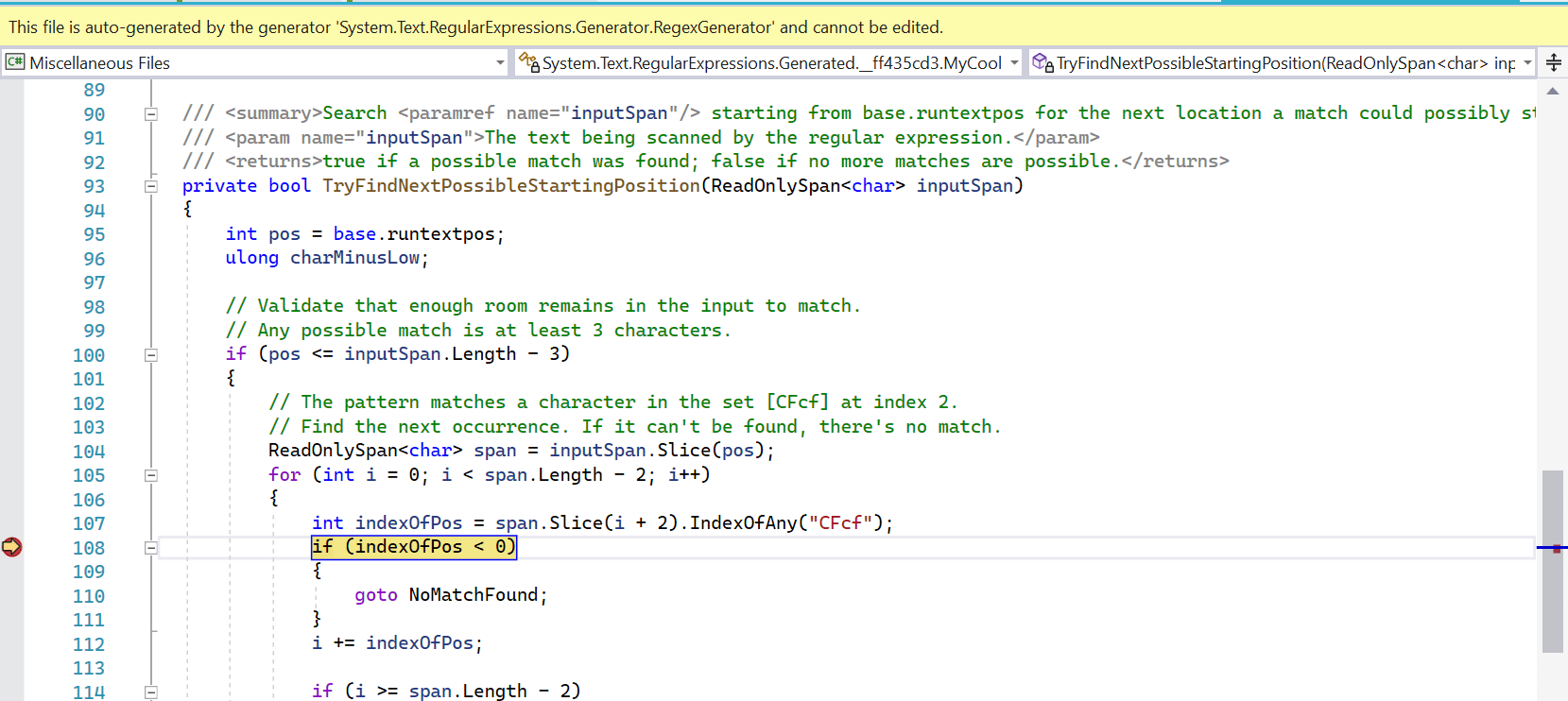

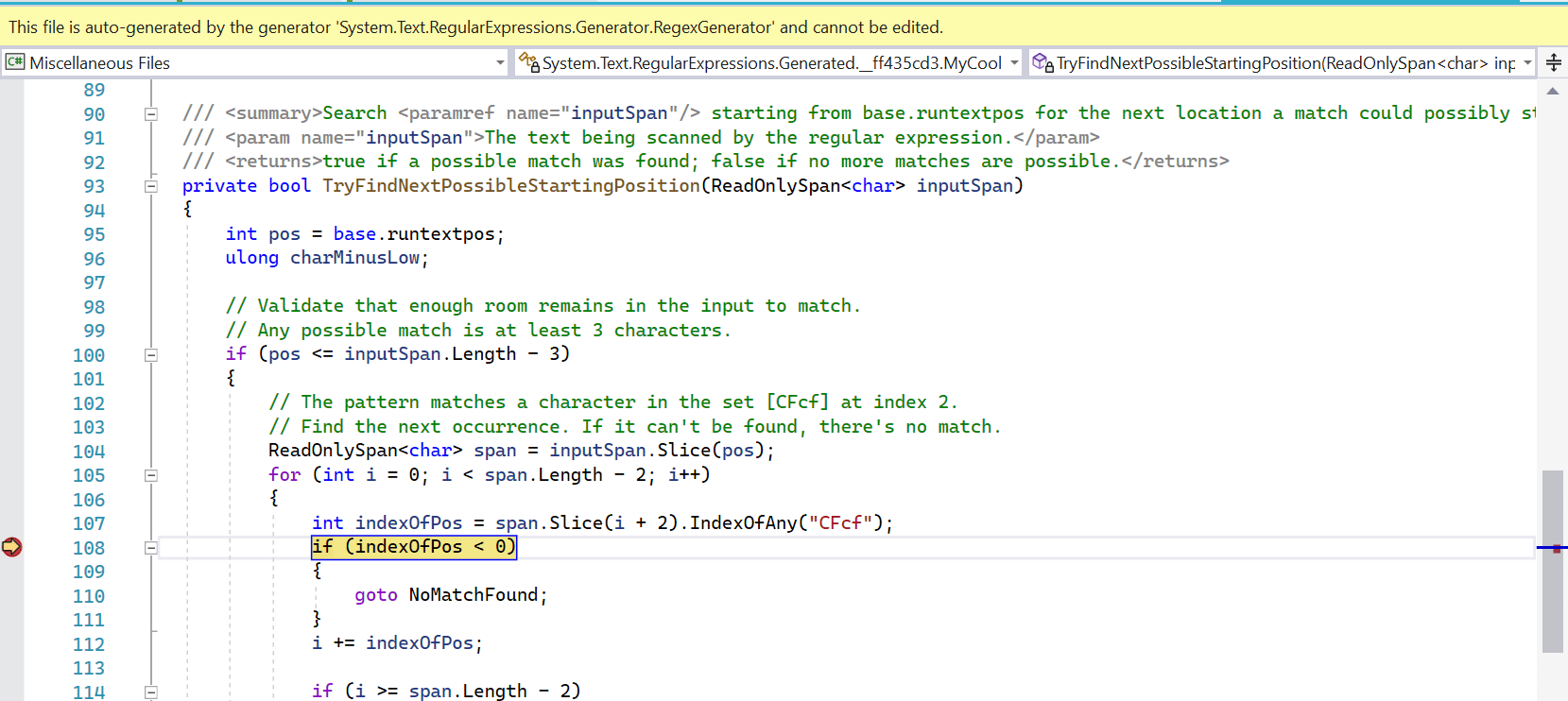

But as can be seen, it's not just doing new Regex(...). Rather, the source generator is emitting as C# code a custom Regex-derived implementation with logic akin to what RegexOptions.Compiled emits in IL. You get all the throughput performance benefits of RegexOptions.Compiled (more, in fact) and the start-up benefits of Regex.CompileToAssembly, but without the complexity of CompileToAssembly. The source that's emitted is part of your project, which means it's also easily viewable and debuggable.

You can set breakpoints in it, you can step through it, and you can use it as a learning tool to understand exactly how the regex engine is processing your pattern and your input. The generator even spits out XML comments in order to help make the expression understandable at a glance at the usage site.

The initial creation of the source generator was a straight port of the RegexCompiler used internally to implement RegexOptions.Compiled; line-for-line, it would essentially just emit a C# version of the IL that was being emitted. Let's take a simple example:

[RegexGenerator(@"(a|bc)d")]

public static partial Regex Example();

Here's what the initial incarnation of the source generator emitted for the core matching routine:

protected override void Go()

{

string runtext = base.runtext!;

int runtextbeg = base.runtextbeg;

int runtextend = base.runtextend;

int runtextpos = base.runtextpos;

int[] runtrack = base.runtrack!;

int runtrackpos = base.runtrackpos;

int[] runstack = base.runstack!;

int runstackpos = base.runstackpos;

int tmp1, tmp2, ch;

// 000000 *Lazybranch addr = 20

L0:

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = runtextpos;

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = 0;

// 000002 *Setmark

L1:

runstack[--runstackpos] = runtextpos;

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = 1;

// 000003 *Setmark

L2:

runstack[--runstackpos] = runtextpos;

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = 1;

// 000004 *Lazybranch addr = 10

L3:

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = runtextpos;

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = 2;

// 000006 One 'a'

L4:

if (runtextpos >= runtextend || runtext[runtextpos++] != 97)

{

goto Backtrack;

}

// 000008 *Goto addr = 12

L5:

goto L7;

// 000010 Multi "bc"

L6:

if (runtextend - runtextpos < 2 ||

runtext[runtextpos] != 'b' ||

runtext[runtextpos + 1] != 'c')

{

goto Backtrack;

}

runtextpos += 2;

// 000012 *Capturemark index = 1

L7:

tmp1 = runstack[runstackpos++];

base.Capture(1, tmp1, runtextpos);

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = tmp1;

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = 3;

// 000015 One 'd'

L8:

if (runtextpos >= runtextend || runtext[runtextpos++] != 100)

{

goto Backtrack;

}

// 000017 *Capturemark index = 0

L9:

tmp1 = runstack[runstackpos++];

base.Capture(0, tmp1, runtextpos);

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = tmp1;

runtrack[--runtrackpos] = 3;

// 000020 Stop

L10:

base.runtextpos = runtextpos;

return;

Backtrack:

int limit = base.runtrackcount * 4;

if (runstackpos < limit)

{

base.runstackpos = runstackpos;

base.DoubleStack(); // might change runstackpos and runstack

runstackpos = base.runstackpos;

runstack = base.runstack!;

}

if (runtrackpos < limit)

{

base.runtrackpos = runtrackpos;

base.DoubleTrack(); // might change runtrackpos and runtrack

runtrackpos = base.runtrackpos;

runtrack = base.runtrack!;

}

switch (runtrack[runtrackpos++])

{

case 0:

{

// 000000 *Lazybranch addr = 20

runtextpos = runtrack[runtrackpos++];

goto L10;

}

case 1:

{

// 000002 *Setmark

runstackpos++;

goto Backtrack;

}

case 2:

{

// 000004 *Lazybranch addr = 10

runtextpos = runtrack[runtrackpos++];

goto L6;

}

case 3:

{

// 000012 *Capturemark index = 1

runstack[--runstackpos] = runtrack[runtrackpos++];

base.Uncapture();

goto Backtrack;

}

default:

{

global::System.Diagnostics.Debug.Fail($"Unexpected backtracking state {runtrack[runtrackpos - 1]}");

break;

}

}

}

That's... intense. But it's the equivalent of what RegexCompiler was producing, essentially walking through the operators/operands created for the interpreter and emitting code for each. There are multiple issues with this. First, it's mostly unintelligible. If one of the goals of the source generator is to emit debuggable code, this largely fails at that goal, as even for someone deeply knowledgable about regular expressions, this isn't going to be very meaningful. Second, there are performance issues; for example, every operation involves pushing and popping state from a "runstack". And third, this loses out on additional possible optimizations, such as being able to use vectorized operations as part of handling specific constructs in the pattern; with this lowered opcode/operand representation, we lose much of the information that could enable the compiler or source generator to add useful improvements based on knowledge of the initial tree.

As such, for .NET 7, after this initial incarnation of the source generator, both the source generator and RegexCompiler were almost entirely rewritten, fundamentally changing the structure of the generated code. In .NET 5, we experimented with an alternative approach, and for simple patterns that didn't involve any backtracking, the RegexCompiler could emit code that was much cleaner, the primary goal being performance. That approach has now been extended to handle all constructs (with one caveat), and both RegexCompiler and the source generator still mapping mostly 1:1 with each other, following the new approach.

Now, here's what the source generator outputs for that same method (which has been renamed) today:

private bool TryMatchAtCurrentPosition(ReadOnlySpan<char> inputSpan)

{

int pos = base.runtextpos;

int matchStart = pos;

int capture_starting_pos = 0;

ReadOnlySpan<char> slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

// 1st capture group.

{

capture_starting_pos = pos;

// Match with 2 alternative expressions.

{

if (slice.IsEmpty)

{

UncaptureUntil(0);

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

switch (slice[0])

{

case 'a':

pos++;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

case 'b':

// Match 'c'.

if ((uint)slice.Length < 2 || slice[1] != 'c')

{

UncaptureUntil(0);

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 2;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

default:

UncaptureUntil(0);

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

}

base.Capture(1, capture_starting_pos, pos);

}

// Match 'd'.

if (slice.IsEmpty || slice[0] != 'd')

{

UncaptureUntil(0);

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

// The input matched.

pos++;

base.runtextpos = pos;

base.Capture(0, matchStart, pos);

return true;

}

That's a whole lot more understandable, with a much more followable structure, with comments explaining what's being done at each step, and in general with code emitted under the guiding principle that we want the generator to emit code as if a human had written it. Even when backtracking is involved, the structure of the backtracking gets baked into the structure of the code, rather than relying on a stack to indicate where to jump next. For example, here's the code for the same generated matching function when the expression is [ab]*[bc]:

private bool TryMatchAtCurrentPosition(ReadOnlySpan<char> inputSpan)

{

int pos = base.runtextpos;

int matchStart = pos;

int charloop_starting_pos = 0, charloop_ending_pos = 0;

ReadOnlySpan<char> slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

// Match a character in the set [ab] greedily any number of times.

//{

charloop_starting_pos = pos;

int iteration = 0;

while ((uint)iteration < (uint)slice.Length && (((uint)slice[iteration]) - 'a' <= (uint)('b' - 'a')))

{

iteration++;

}

slice = slice.Slice(iteration);

pos += iteration;

charloop_ending_pos = pos;

goto CharLoopEnd;

CharLoopBacktrack:

if (Utilities.s_hasTimeout)

{

base.CheckTimeout();

}

if (charloop_starting_pos >= charloop_ending_pos ||

(charloop_ending_pos = inputSpan.Slice(charloop_starting_pos, charloop_ending_pos - charloop_starting_pos).LastIndexOfAny('b', 'c')) < 0)

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

charloop_ending_pos += charloop_starting_pos;

pos = charloop_ending_pos;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

CharLoopEnd:

//}

// Advance the next matching position.

if (base.runtextpos < pos)

{

base.runtextpos = pos;

}

// Match a character in the set [bc].

if (slice.IsEmpty || (((uint)slice[0]) - 'b' > (uint)('c' - 'b')))

{

goto CharLoopBacktrack;

}

// The input matched.

pos++;

base.runtextpos = pos;

base.Capture(0, matchStart, pos);

return true;

}

You can see the structure of the backtracking in the code, with a CharLoopBacktrack label emitted for where to backtrack to and a goto used to jump to that location when a subsequent portion of the regex fails.

If you look at the code implementing RegexCompiler and the source generator, they will look extremely similar: similarly named methods, similar call structure, even similar comments throughout the implementation. For the most part, they spit identical code, albeit one in IL and one in C#. Of course, the C# compiler is then responsible for translating the C# into IL, so the resulting IL in both cases likely won't be identical. In fact, the source generator relies on that in various cases, taking advantage of the fact that the C# compiler will further optimize various C# constructs. There are a few specific things the source generator will thus produce more optimized matching code for than does RegexCompiler. For example, in one of the previous examples, you can see the source generator emitting a switch statement, with one branch for 'a' and another branch for 'b'. Because the C# compiler is very good at optimizing switch statements, with multiple strategies at its disposal for how to do so efficiently, the source generator has a special optimization that RegexCompiler does not. For alternations, the source generator looks at all of the branches, and if it can prove that every branch begins with a different starting character, it will emit a switch statement over that first character and avoid outputting any backtracking code for that alternation (since if every branch has a different starting first character, once we enter the case for that branch, we know no other branch could possibly match).

Here's a slightly more complicated example of that. In .NET 7, alternations are more heavily analyzed to determine whether it's possible to refactor them in a way that will make them more easily optimized by the backtracking engines and that will lead to simpler source-generated code. One such optimization supports extracting common prefixes from branches, and if the alternation is atomic such that ordering doesn't matter, reordering branches to allow for more such extraction. We can see the impact of that for a weekday pattern Monday|Tuesday|Wednesday|Thursday|Friday|Saturday|Sunday, which produces a matching function like this:

private bool TryMatchAtCurrentPosition(ReadOnlySpan<char> inputSpan)

{

int pos = base.runtextpos;

int matchStart = pos;

ReadOnlySpan<char> slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

// Match with 5 alternative expressions, atomically.

{

if (slice.IsEmpty)

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

switch (slice[0])

{

case 'M':

// Match the string "onday".

if (!slice.Slice(1).StartsWith("onday"))

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 6;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

case 'T':

// Match with 2 alternative expressions, atomically.

{

if ((uint)slice.Length < 2)

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

switch (slice[1])

{

case 'u':

// Match the string "esday".

if (!slice.Slice(2).StartsWith("esday"))

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 7;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

case 'h':

// Match the string "ursday".

if (!slice.Slice(2).StartsWith("ursday"))

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 8;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

default:

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

}

break;

case 'W':

// Match the string "ednesday".

if (!slice.Slice(1).StartsWith("ednesday"))

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 9;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

case 'F':

// Match the string "riday".

if (!slice.Slice(1).StartsWith("riday"))

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 6;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

case 'S':

// Match with 2 alternative expressions, atomically.

{

if ((uint)slice.Length < 2)

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

switch (slice[1])

{

case 'a':

// Match the string "turday".

if (!slice.Slice(2).StartsWith("turday"))

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 8;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

case 'u':

// Match the string "nday".

if (!slice.Slice(2).StartsWith("nday"))

{

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

pos += 6;

slice = inputSpan.Slice(pos);

break;

default:

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

}

break;

default:

return false; // The input didn't match.

}

}

// The input matched.

base.runtextpos = pos;

base.Capture(0, matchStart, pos);

return true;

}

Note how Thursday was reordered to be just after Tuesday, and how for both the Tuesday/Thursday pair and the Saturday/Sunday pair, we end up with multiple levels of switches. In the extreme, if you were to create a long alternation of many different words, the source generator would end up emitting the logical equivalent of a trie, reading each character and switch'ing to the branch for handling the remainder of the word.

At the same time, the source generator has other issues to contend with that simply don't exist when outputting to IL directly. If you look a couple of code examples back, you can see some braces somewhat strangely commented out. That's not a mistake. The source generator is recognizing that, if those braces weren't commented out, the structure of the backtracking would be relying on jumping from outside of a scope to a label defined inside of that scope; such a label would not be visible to such a goto and the code would fail to compile. Thus, the source generator needs to avoid there actually being a scope in the way. In some cases, it'll simply comment out the scope as was done here. In other cases where that's not possible, it may sometimes avoid constructs that require scopes (e.g. a multi-statement if block) if doing so would be problematic.

The source generator handles everything RegexCompiler handles, with one exception. Earlier in this post we discussed the new approach to handling RegexOptions.IgnoreCase, how the implementations now use a casing table to generate sets at construction time, and how IgnoreCase backreference matching needs to consult that casing table. That table is internal to System.Text.RegularExpressions.dll, and for now at least, code external to that assembly (including code emitted by the source generator) does not have access to it. That makes handling IgnoreCase backreferences a challenge in the source generator. We could choose to also output the casing table if it's required, but it's quite a hefty chunk of data to blit into consuming assemblies. So at least for now, IgnoreCase backreferences are the one construct not supported by the source generator that is supported by RegexCompiler. If you try to use a pattern that has one of these (which, at least according to our research, are very rare), the source generator won't emit a custom implementation and will instead fall back to caching a regular Regex instance:

Also, neither RegexCompiler nor the source generator support the new RegexOptions.NonBacktracking. If you specify RegexOptions.Compiled | RegexOptions.NonBacktracking, the Compiled flag will just be ignored, and if you specify NonBacktracking to the source generator, it will similarly fall back to caching a regular Regex instance. (It's possible the source generator will support NonBacktracking as well in the future, but that's unlikely to happen for .NET 7.)

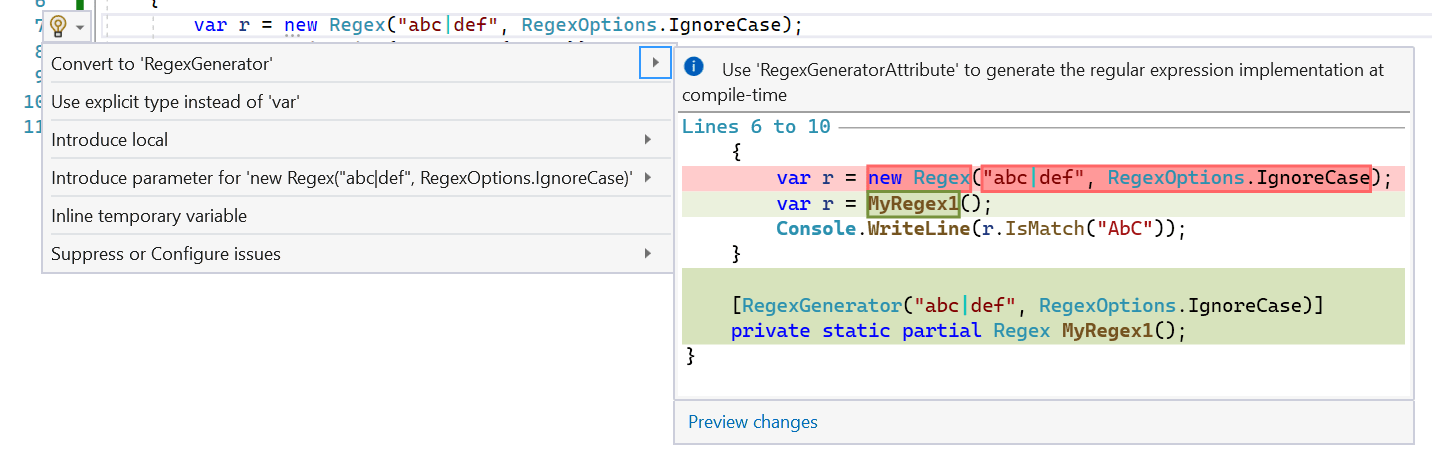

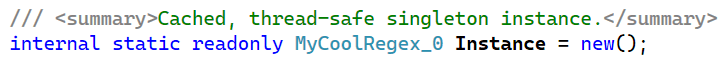

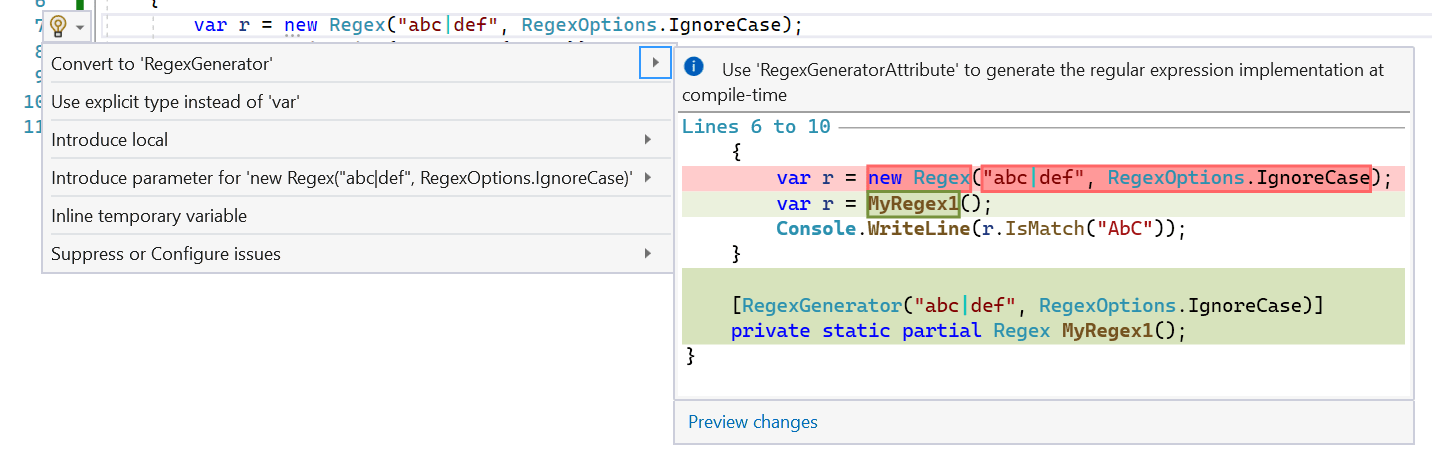

Finally, the $10 million dollar question: when should you use the source generator? The general guidance is, if you can use it, use it. If you're using Regex today in C# with arguments known at compile-time, and especially if you're already using RegexOptions.Compiled (because the regex has been identified as a hot spot that would benefit from faster throughput), you should prefer to use the source generator. The source generator will give your regex all the throughput benefits of RegexOptions.Compiled, the startup benefits of not having to do all the regex parsing, analysis, and compilation at runtime, the option of using ahead-of-time compilation with the code generated for the regex, better debugability and understanding of the regex, and even the possibility to reduce the size of your trimmed app by trimming out large swaths of code associated with RegexCompiler (and potentially even reflection emit itself). And even if used with an option like RegexOptions.NonBacktracking for which it can't yet generate a custom implementation, it will still helpfully emit caching, XML comments describing the implementation, and so on, such that it's still valuable. The main downside of the source generator is that it is emitting additional code into your assembly, so there's the potential for increased size; the more regexes in your app and the larger they are, the more code will be emitted for them. In some situations, just as RegexOptions.Compiled may be unnecessary, so too may be the source generator, e.g. if you have a regex that's needed only rarely and for which throughput doesn't matter, it could be more beneficial to just rely on the interpreter for that sporadic usage. However, we're so confident in the general "if you can use it, use it" guidance that .NET 7 will also include an analyzer that identifies use of Regex that could be converted to the source generator, and a fixer that does the conversion for you:

Spans

Span<T> and ReadOnlySpan<T> have fundamentally transformed how code gets written in .NET, especially in higher-performance scenarios. These types make it easy to implement a single algorithm that's able to process strings, arrays, slices of data, stack-allocated state, or native memory, all behind a fast, optimized veneer. Hundreds of methods in the core libraries now accept spans, and ever since spans were introduced in .NET Core 2.1, developers have been asking for span support in Regex. This has been challenging to accomplish for two main reasons.

The first issue is Regex's extensibility model. The aforementioned Regex.CompileToAssembly generated a Regex-derived type that needed to be able to plug its logic into the general scaffolding of the regex system, e.g. you call a method on the Regex instance, like IsMatch, and that needs to find its way into the code emitted by CompileToAssembly. To achieve that, System.Text.RegularExpressions exposes an abstract RegexRunner type, which exposes a few abstract methods, most importantly FindFirstChar and Go. All of the engines plug into the execution via RegexRunner: the internal RegexInterpreter derives from RegexRunner and overrides those methods to implement the regex by interpretering the opcodes/operands written during construction, the NonBacktracking engine has a type that derives from RegexRunner, and RegexCompiler ends up creating delegates to DynamicMethods it reflection emits and creates an instance of a type derived from RegexRunner that will invoke those delegates. The source generator also emits code that plugs in the same way. The problem as it relates to span, though, is how to get the span into these methods. RegexRunner is a class and can't store a span as a field, and these FindFirstChar and Go methods were long-since defined and don't accept a span as an argument. As such, with the shape of this model as it's been defined for nearly 20 years, there's no way to get a span into the code that would process it.

The second issue is around the API for returning results. IsMatch is simple: it just returns a bool. But Match and Matches are both based on returning objects that represent matches, and such objects can't hold a reference to a span. That's an issue, because the mechanism by which the current model supports iterating through results is lazy, with the first match being computed, and then using the resulting Match's NextMatch() method to pick up where the first operation left off. If that Match can't store the input span, it can't provide it back to the engine for subsequent matching.

In .NET 7, we've tackled these issues, such that Regex in .NET 7 now supports span inputs, at least with some of the APIs. Overloads of IsMatch accept ReadOnlySpan<char>, as do overloads of two new methods: Count and EnumerateMatches. This means you can now use the .NET Regex type with data stored in a char[], or data from a char* passed via interop, or data from a ReadOnlySpan<char> sliced from a string, or from anywhere else you may have received a span.

The new Count method takes a string or a ReadOnlySpan<char>, and returns an int for how many matches exist in the input text; previously if you wanted to do this, you could have written code that iterated using Match and NextMatch(), but the built-in implementation is leaner and faster (and doesn't require you to have to write that out each time you need it, and works with spans). The performance benefits are obvious from a microbenchmark:

private Regex _r = new Regex("a", RegexOptions.Compiled);

private string _input = new string('a', 1000);

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int Match()

{

int count = 0;

Match m = _r.Match(_input);

while (m.Success)

{

count++;

m = m.NextMatch();

}

return count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Count() => _r.Count(_input);

which on my machine yields results like this:

| Method |

Mean |

Ratio |

Allocated |

| Match |

75.00 us |

1.00 |

208000 B |

| Count |

32.07 us |

0.43 |

- |

The more interesting method, though, is EnumerateMatches. EnumerateMatches accepts a string or a ReadOnlySpan<char> and returns a ref struct enumerator that can store the input span and thus is able to lazily enumerate all the matches in the input.

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

ReadOnlySpan<char> text = "Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day";

foreach (ValueMatch m in Regex.EnumerateMatches(text, @"\b\w+\b"))

{

Console.WriteLine($"Word: {text.Slice(m.Index, m.Length)}");

}

One of the interesting things about both Count and EnumerateMatches (and the existing Replace when not employing backreferences in the replacement pattern) is that they can be much more efficient than Match or Matches in terms of the work required for an engine. In particular, the NonBacktracking engine is implemented in a fairly pay-for-play manner: the less information you need, the less work it has to do. So with IsMatch only requiring the engine to compute whether there exists a match, NonBacktracking can get away with doing much less work than for Match, where it needs to compute the exact offset and length of the match and also compute all of the subcaptures. Neither Count nor EnumerateMatches requires computing the captures information, however, and thus can save NonBacktracking a non-trivial amount of work. Here's a microbenchmark to highlight the differences:

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Running;

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

[MemoryDiagnoser]

public class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args) => BenchmarkSwitcher.FromAssembly(typeof(Program).Assembly).Run(args);

private static string s_text = """

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm'd;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

""";

private readonly Regex _words = new Regex(@"b(\w+)b", RegexOptions.NonBacktracking);

[Benchmark]

public int Count() => _words.Count(s_text);

[Benchmark]

public int EnumerateMatches()

{

int count = 0;

foreach (ValueMatch _ in _words.EnumerateMatches(s_text))

{

count++;

}

return count;

}

[Benchmark]

public int Match()

{

int count = 0;

Match m = _words.Match(s_text);

while (m.Success)

{

count++;

m = m.NextMatch();

}

return count;

}

}

which on my machine yields results like these:

| Method |

Mean |

Allocated |

| Count |

26,736.0 ns |

- |

| EnumerateMatches |

28,680.5 ns |

- |

| Match |

82,351.7 ns |

30256 B |

Note that Count and EnumerateMatches are much faster than Match, as Match needs to compute the captures information, whereas Count and EnumerateMatches only need to compute the bounds of the match. Also note that both Count and EnumerateMatches end up being ammortized allocation-free.

So, spans are supported, yay. You can see we overcame the second highlighted issue by creating a new EnumerateMatches method that doesn't return a class Match and instead returns a ref struct ValueMatch. But what about the first issue? To address that, we introduced a new virtual Scan(ReadOnlySpan<char>) method on RegexRunner, and changed the existing abstract methods to be virtual (they now exist only for compatibility with any CompileToAssembly assemblies that might still be in use), such that Scan is the only method that now need be overridden by the source generator. If we try a sample like:

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

partial class Program

{

public static void Main() => Console.WriteLine(Example().IsMatch("aaaabbbb"));

[RegexGenerator(@"a*b", RegexOptions.IgnoreCase, -1)]

private static partial Regex Example();

}

we can see the source generator spits out a RegexRunner-derived type that overrides Scan:

/// <summary>Scan the <paramref name="inputSpan"/> starting from base.runtextstart for the next match.</summary>

/// <param name="inputSpan">The text being scanned by the regular expression.</param>

protected override void Scan(ReadOnlySpan<char> inputSpan)

{

// Search until we can't find a valid starting position, we find a match, or we reach the end of the input.

while (TryFindNextPossibleStartingPosition(inputSpan) &&

!TryMatchAtCurrentPosition(inputSpan) &&

base.runtextpos != inputSpan.Length)

{

base.runtextpos++;

}

}

With that, the public APIs on Regex can accept a span and pass it all the way through to the engines for them to process the input. And the engines are all then fully implemented in terms of only span. This has itself served to clean up the implementations nicely. Previously, for example, the implementations needed to be concerned with tracking both a beginning and ending position within the supplied string, but now the span that's passed in represents the entirety of the input to be considered, so the only bounds that are relevant are those of the span itself.

Vectorization

As noted earlier when talking about IgnoreCase, vectorization is the idea that we can process multiple pieces of data at the same time with the same instructions (also known as "SIMD", or "single instruction multiple data"), thereby making the whole operation go much faster. .NET 5 introduced a bunch of places where vectorization was employed. .NET 7 takes that significantly further.

Leading Vectorization

One of the most important places for vectorization in a regex engine is when finding the next location a pattern could possibly match. For longer input text being searched, the time to find matches is frequently dominated by this aspect. As such, as of .NET 6, Regex had various tricks in place to get to those locations as quickly as possible:

- Anchors. For patterns that began with an anchor, it could either avoid doing any searching if there was only one place the pattern could possibly begin (e.g. a "beginning" anchor, like

^ or A), and it could skip past text it knew couldn't match (e.g. IndexOf('\n') for a "beginning-of-line" anchor if not currently at the beginning of a line).

- Boyer-Moore. For patterns beginning with a sequence of at least two characters (case-sensitive or case-insensitive), it could use a Boyer-Moore search to find the next occurrence of that sequence in the input text.

- IndexOf(char). For patterns beginning with a single case-sensitive character, it could use

IndexOf(char) to find the next possible match location.

- IndexOfAny(char, char, ...). For patterns beginning with one of only a few case-sensitive characters, it could use

IndexOfAny(...) with those characters to find the next possible match location.

These optimizations are all really useful, but there are many additional possible solutions that .NET 7 now takes advantage of:

- Goodbye, Boyer-Moore.

Regex has used the Boyer-Moore algorithm since Regex's earliest days; the RegexCompiler even emitted a customized implementation in order to maximize throughput. However, Boyer-Moore was created at a time when vector instruction sets weren't yet a reality. Most modern hardware can examine 8 or 16 16-bit chars in just a few instructions, whereas with Boyer-Moore, it's rare to be able to skip that many at a time (the most it can possibly skip at a time is the length of the substring for which it's searching). In the aforementioned corpus of ~19,000 regular expressions, ~50% of those expressions that begin with a case-sensitive prefix of at least two characters have a prefix less than or equal to four characters, and ~75% are less than or equal to eight characters. Moreover, the Boyer-Moore algorithm works by choosing a single character to examine in order to perform each jump, but a well-vectorized algorithm can simultaneously compare multiple characters, such as the first and last in the prefix (as described in SIMD-friendly algorithms for substring searching), enabling it to stay in the inner vectorized loop longer. In .NET 7, IndexOf performing an ordinal search for a string has been significantly improved with such tricks, and now in .NET 7, Regex uses IndexOf rather than Boyer-Moore, the implementation of which has been deleted (this was inspired by Rust's regex crate making a similar change last year). You can see the impact of this on a microbenchmark like the following, which is finding every word in a document, creating a Regex for that word, and then using each Regex to find all occurrences of each word in the document (this would be an ideal use for the new Count method, but I'm not using it here as it doesn't exist in the previous releases being compared):

private string _text;

private Regex[] _words;

[Params(false, true)]

public bool IgnoreCase { get; set; }

[GlobalSetup]

public async Task Setup()

{

using var hc = new HttpClient();

_text = await hc.GetStringAsync(@"https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1661/1661-0.txt");

_words = Regex

.Matches(_text, @"\b\w+\b")

.Cast()

.Select(m => m.Value)

.Distinct(IgnoreCase ? StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase : StringComparer.Ordinal)

.Select(s => new Regex(Regex.Escape(s), RegexOptions.Compiled | (IgnoreCase ? RegexOptions.IgnoreCase | RegexOptions.CultureInvariant : RegexOptions.None)))

.ToArray();

}

[Benchmark]

public int FindAllOccurrencesOfAllWords()

{

int count = 0;

foreach (Regex word in _words)

{

Match m = word.Match(_text);

while (m.Success)

{

count++;

m = m.NextMatch();

}

}

return count;

}

On my machine, I get numbers like this:

| Method |

Runtime |

IgnoreCase |

Mean |

Ratio |

| FindAllOccurrencesOfAllWords |

.NET Framework 4.8 |

False |

7,657.1 ms |

1.00 |

| FindAllOccurrencesOfAllWords |

.NET 6.0 |

False |

5,056.5 ms |

0.66 |

| FindAllOccurrencesOfAllWords |

.NET 7.0 |

False |

522.3 ms |

0.07 |

| FindAllOccurrencesOfAllWords |

.NET Framework 4.8 |

True |

12,624.1 ms |

1.00 |

| FindAllOccurrencesOfAllWords |

.NET 6.0 |

True |

5,649.4 ms |

0.45 |

| FindAllOccurrencesOfAllWords |

.NET 7.0 |

True |

1,649.1 ms |

0.13 |

Even when compared against an optimized string searching algorithm like Boyer-Moore, this really highlights the power of vectorization.

- IndexOfAny in More Cases. As noted, .NET 6 supports using

IndexOfAny to find the next matching location when a match can begin with a small set, specifically a set with two or three characters in it. This limit was chosen because IndexOfAny only has public overloads that take two or three values. However, IndexOfAny also has an overload that takes a ReadOnlySpan<T> of the values to find, and as an implementation detail, it actually vectorizes the search for up to five. So in .NET 7, we'll use that span-based overload for sets with four or five characters, expanding the reach of this valuable optimization.

private static Regex s_regex = new Regex(@"Surname|(Last[_]?Name)", RegexOptions.Compiled | RegexOptions.IgnoreCase);

private static string s_text = @"We're looking through text that might contain a first or last name.";

[Benchmark]

public bool IsMatch() => s_regex.IsMatch(s_text);

| Method |

Runtime |

Mean |

Ratio |

| IsMatch |

.NET Framework 4.8 |

2,429.02 ns |

1.00 |

| IsMatch |

.NET 6.0 |

294.79 ns |

0.12 |

| IsMatch |

.NET 7.0 |

82.84 ns |

0.03 |